I am often asked by non-book collecting friends what makes a book collectible and how can you tell if a book is valuable. Here are some thoughts on these matters.

Firstly, for a book to be collectible, there needs to be someone out there in the world who desires to own it! That may seem obvious, but really is the sine qua non of any collecting. Similarly, one may ask what is a particular book worth, and one rather obvious answer is “Whatever someone in the marketplace for books is prepared to pay for it!”

For instance, a book dealer may have a rare volume displayed in his or her shop with a price tag of say $500 on it, but if the book has been unsold in the shop at that price for 5 years, then who is to say that it is worth the price on the tag?

If we dig a little deeper into these issues, the four major determinants of “worth”, which may not be the same thing as “value” or “price” are form, content, rarity and condition. Lets consider these four issues in turn.

Form

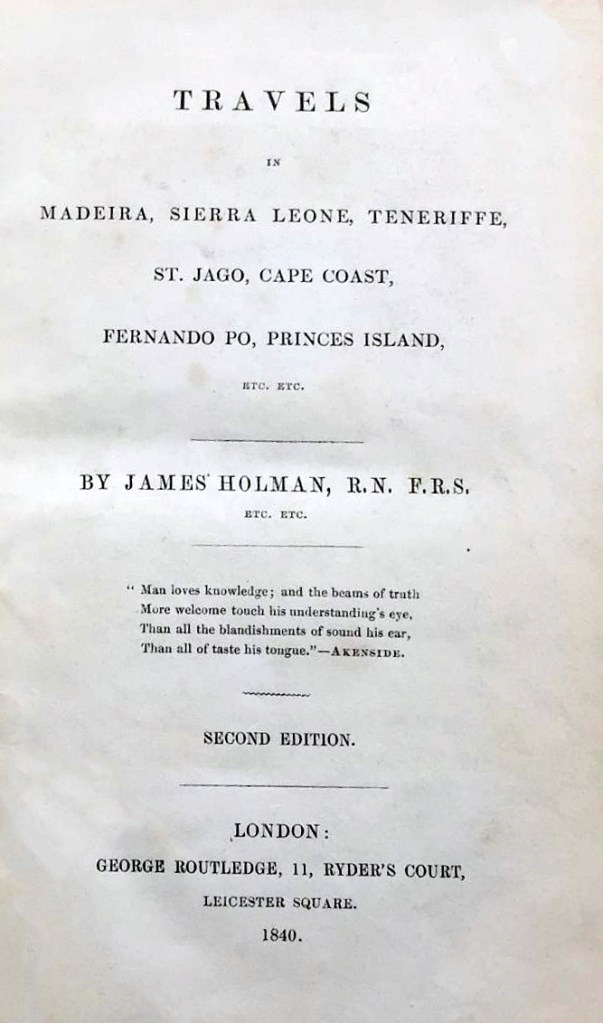

By form, I mean the physical presentation of the book. Is it a hardback or paperback? Is it a first edition or a reprint? Is it printed or published by a desirable firm? Is it in an attractive or elegant binding? Is it illustrated? Is it signed by anyone special, such as the author, illustrator or a significant previous owner? Does it have an interesting, well designed or famous bookplate? Some of these issues is worthy of some consideration.

Hardback or Paperback

Generally speaking, hardback, or more properly, ‘cased’ books are more collectible than paperbacks. There are many reasons for this. Most books are first published in a fully bound and cased format, at a relatively higher price, before they are then reprinted as a less expensive paperback in card covers, often with the gatherings of the pages glued to a back-strip, in what is misleadingly called ‘perfect bound’. Most paperbacks that one sees are perfect bound. In recent years, in an attempt to contain costs, large format first edition ‘trade paperbacks’ have been published at the same time as an equivalent fully cased hardback first edition. Here in Australia, for instance, in the 21st century, most first edition novels are only available as trade paperbacks, when in the UK and USA they are often published as both hardbacks and trade paperbacks. Often it is then only the trade paperback that is exported from the UK to Australia for retail sale.

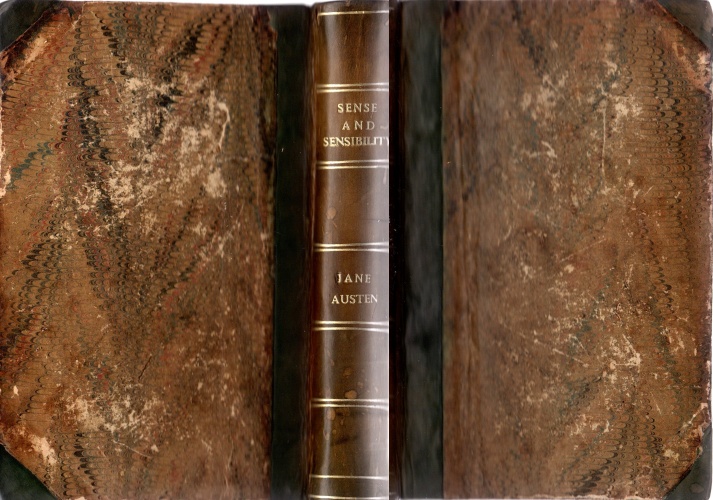

Cased books for the last almost 200 years have been bound within board covers that are covered with a substance that can be labelled or decorated. The coverings were traditionally types of animal skins, leathers of various types, or vellum. In the early 19th century, book cloth was popularised as a cheaper and durable alternative to animal products.

Since the later part of the 19th century, cased books have also been covered by paper wrappers called a dust wrapper or dust jacket. These were initially disposable, plain paper covers to protect the printed pages before they were cased by a book binder, or to protect them on the journey between the publisher and the retail bookseller. As the years went by, the dust jackets were seen as a useful, if perhaps ephemeral part of the book, which could also be decorated and so be useful in the marketing of books. For the collector of Modern First Editions (however defined), the dust jacket is a highly desirable if not essential component of the book for it to be deemed complete and collectible.

Some paperbacks are highly prized and collectible, particularly certain books which were only published in paperback format, or books from certain paperback publishers, such as Penguin, Albatross, Tauchnitz and Pan.

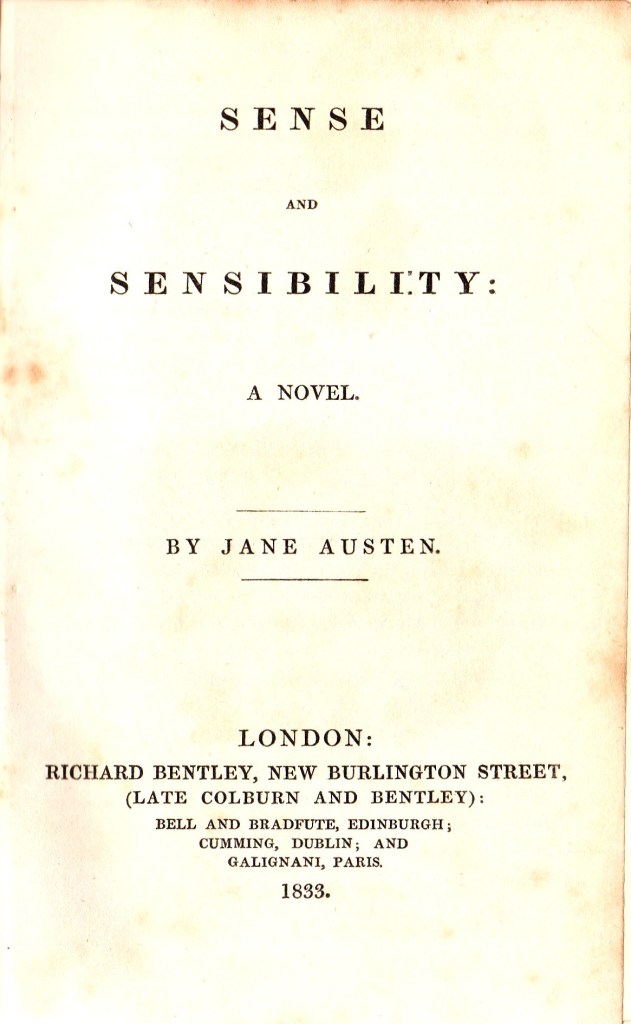

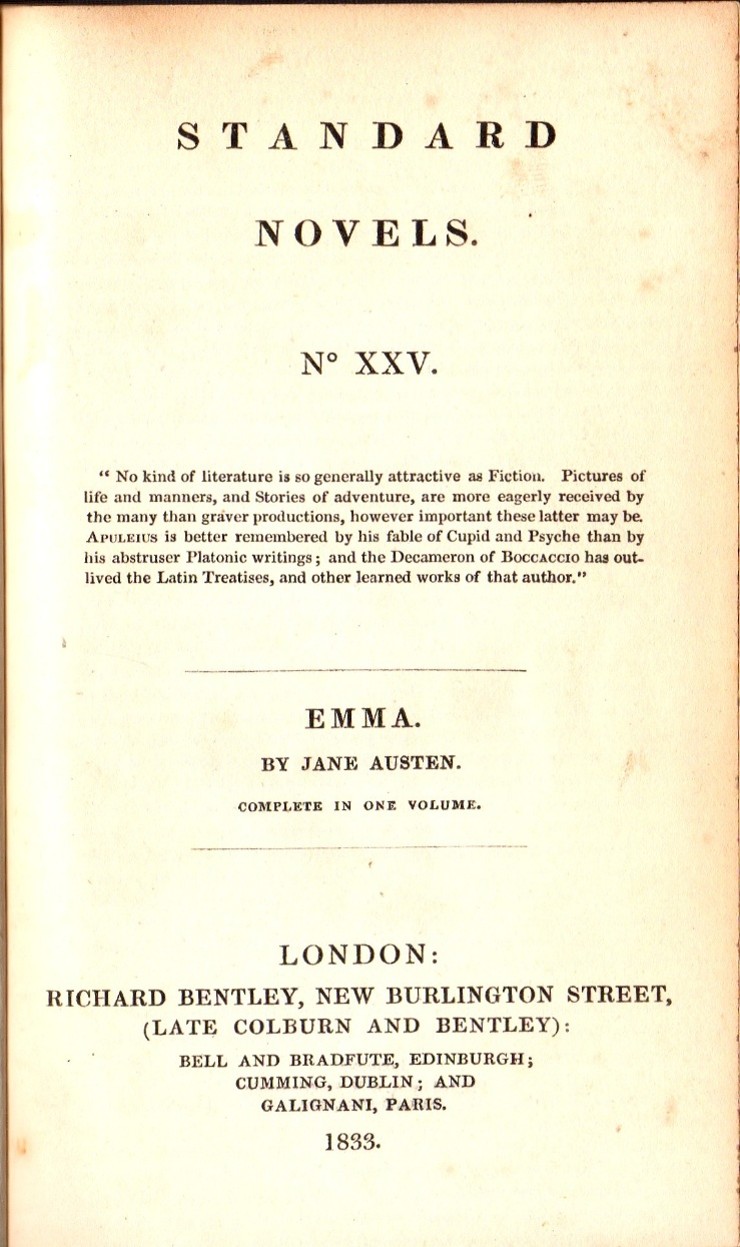

First editions

Everyone knows that first editions are very collectible and are often highly desired. But if you give this a little thought, it does require some explanation. One thing that you can be sure of is that every book that has ever been published has existed as a first edition. Indeed, the vast majority of books, once published in their first edition, have probably failed to sell sufficiently well, and so have never been reprinted or re-issued! So why the importance of first editions? Collectors will generally say that the first edition is the first appearance of the book and as the initial form of the book that the world ever sees, it has a particular power and importance beyond the raw text. They will also say that the first edition also represents the author’s freshest and new ideas and inventions. However, the first appearance of a book, which is strictly the first state of the first impression of the first edition ( I will explore these terms more in a following blog) in the original publisher’s binding and dust jacket will often contain errors (known in the book collecting world as points) that are most commonly introduced by the printer, but sometimes by the editor or the binder. Thus the earliest form of the book may not represent the author’s true intentions, and it may be later states that correctly reflect the text as presented in the author’s manuscript.

Bindings

Generally, the original publisher’s binding of a book is the most desired form. However, from the earliest times, it has been quite common for books to be given different bindings after their purchase, that are often more ornate and attractive than the publisher’s binding. Sometimes, particular book buyers or collectors had a preferred or personalised form of binding that they always applied to their books. Some private, public and school libraries also adopted this practice. From early Victorian times, it was quite common to replace the publisher’s cloth binding with a half or quarter bound casing that used different leathers and boards, often with marbled end papers. On occasions, the publishers themselves produce a limited number of copies of a book that are bound in higher quality, more expensive bindings.

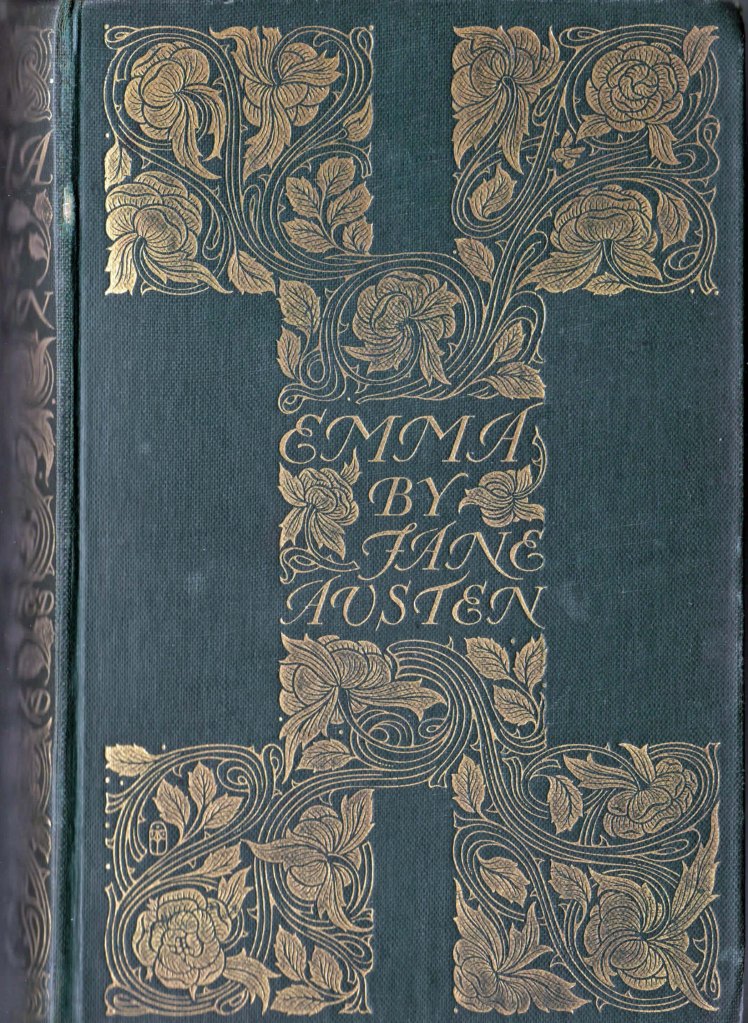

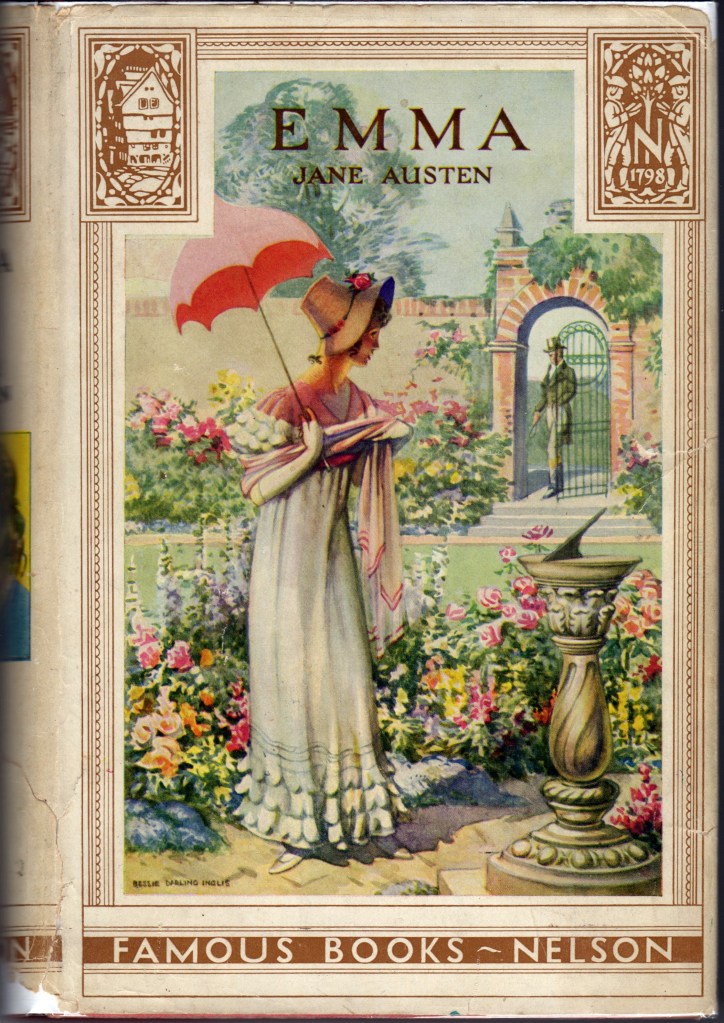

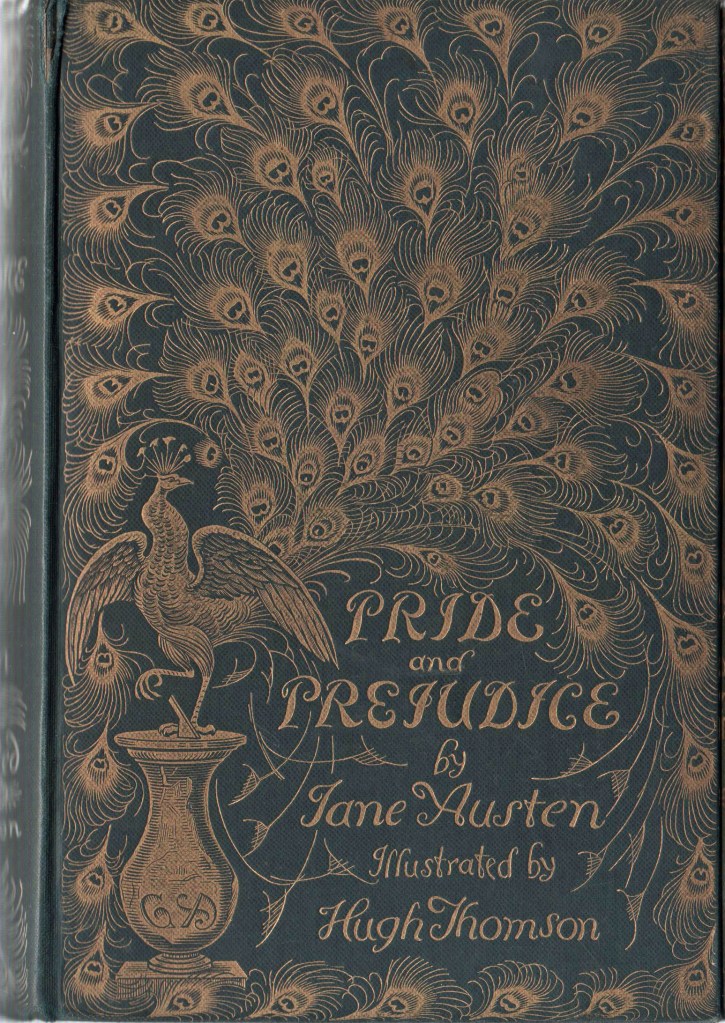

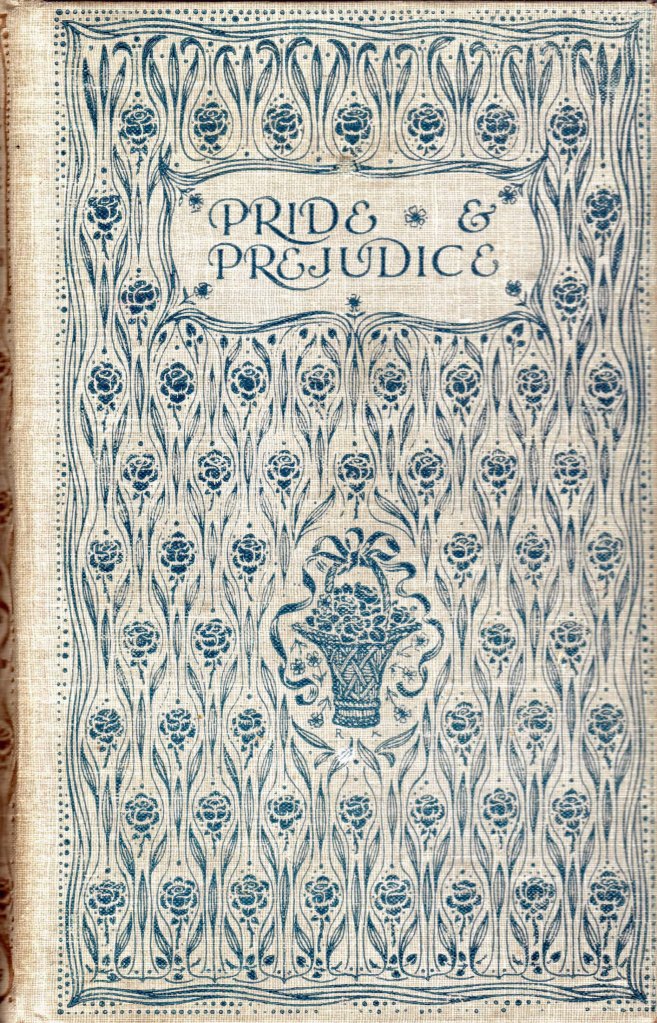

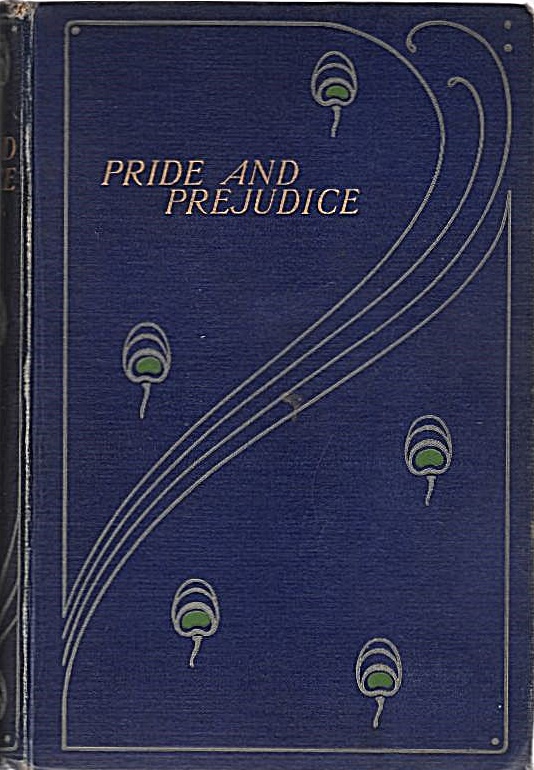

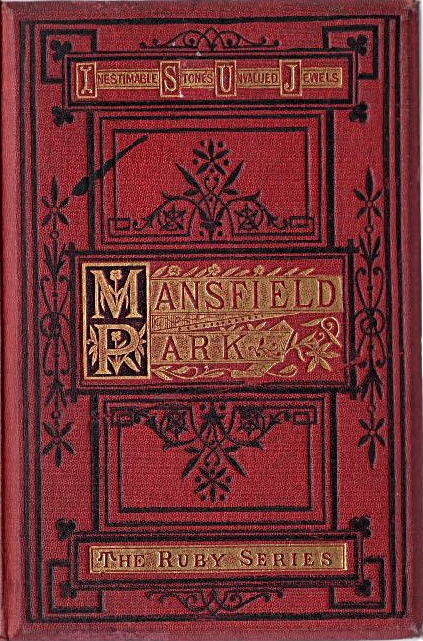

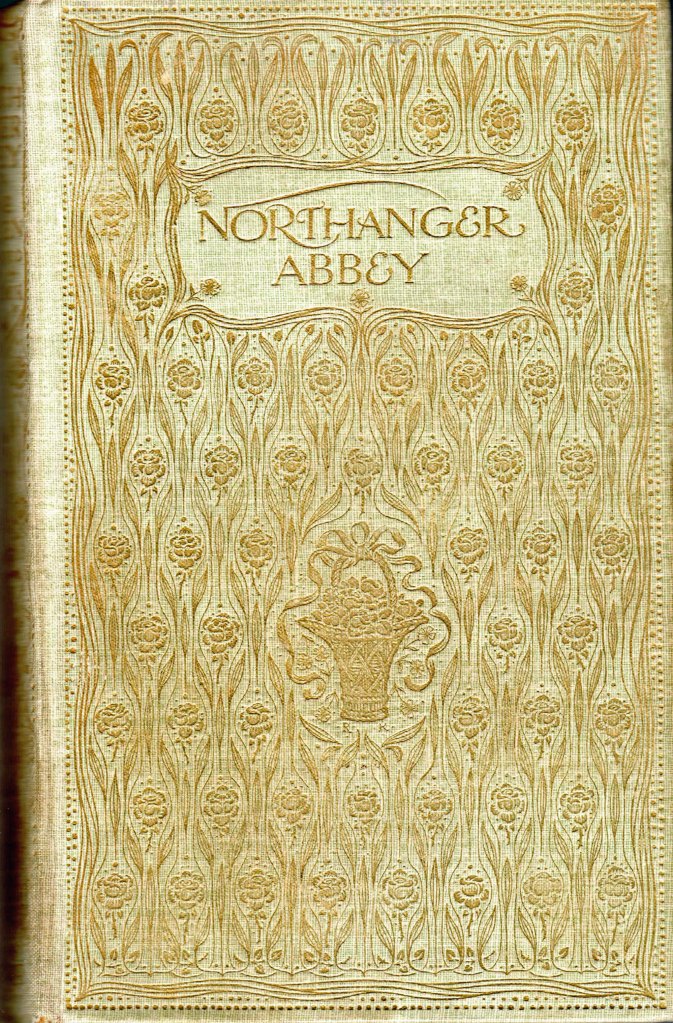

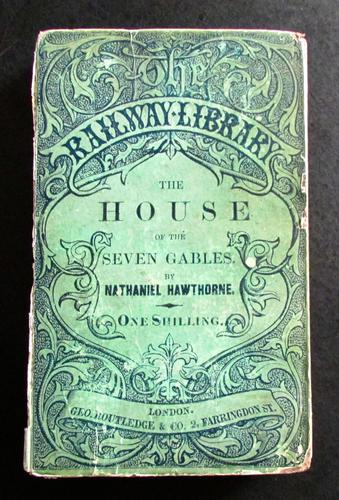

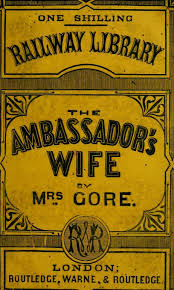

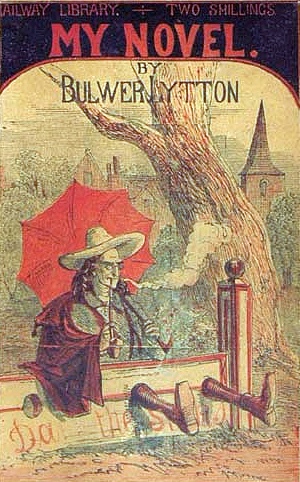

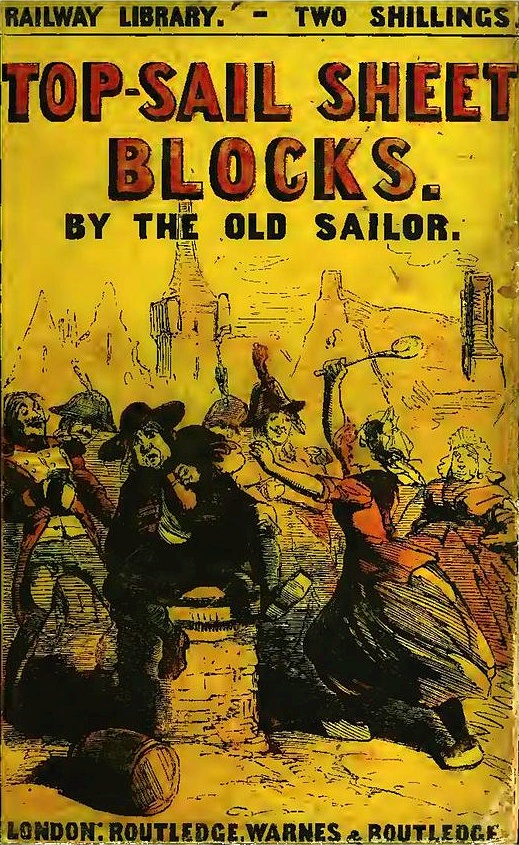

In mid to late Victorian times, many publishers adopted more highly decorated cloth styles, with the use of impressed or embossed gilt designs or coloured cloth decorations, sometimes on beveled or more elaborately incised boards. All of these superior Victorian cloth bindings are very collectible in their own right. In addition the cheap ‘yellowback’ bindings of crime and sensational novels of the late Victorian and Edwardian age are also now highly collected.

From the early years of the twentieth century, books were mostly bound in cloth which had become very plain and undecorated, particularly after World War One. As the cloth became plainer, so the dust jackets gradually became more highly decorated. In the Art Deco period, from the early-1920s until the end of the thirties, an expectation of elegantly decorated dust jackets began to become the norm for high quality books. For some crime fiction and thrillers, some of the dust jacket decorations became quite lurid and sensational. There are collectors out there for all of these. A few authors even designed their own dust jackets, Evelyn Waugh with ‘Vile Bodies‘ and Ian Fleming with ‘Moonraker‘ are two famous examples, and Len Deighton designed a few decorated Penguin covers in the 1960s.

Signed books

Names or signatures in books can add to their desirability. However, it does matter whose name and signature it is. ” To little Freddy from Auntie Nell, Xmas 1984, XXX “, scrawled across the title page of any book with purple broad tip Texta pen will almost certain detract from the books desirability.

However, a copy of the James Bond book ‘Dr No‘, neatly signed “Ian Fleming” on the end-paper would be desirable. If it were inscribed “Peter, here is my latest book; your brother Ian” it would probably be more desirable. If it were to be signed “to Sean Connery from Ian Fleming, loved your performance”, it would be very highly desirable. I’m sure that you get the idea. Certainly a plain signature, probably written en masse for a bookstore appearance, is probably less desirable that a dedication to an unknown person, and certainly less desirable than a dedication to a famous person or a person who has some significant relationship to the book.

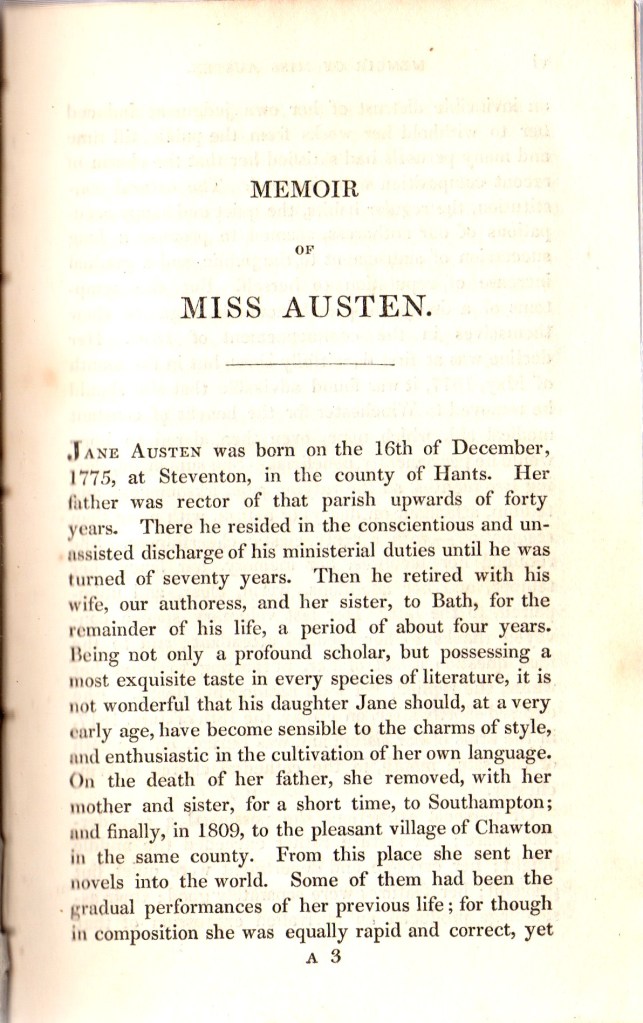

Ownership signatures from famous, previous owners of the book, neatly written on an end-paper are also highly desirable. In this regard, a copy of Hitler’s “Mein Kampf”, with Sir Winston Churchill’s ownership signature would be desired by all collectors of war books or Churchilliana.

Bookplates

Bookplates are the often decorative labels pasted onto the end-papers of books to assert ownership. Many people had personalised bookplates designed for them and the presence of a discreet and tasteful book plate does not generally lessen the desirability of a book; if the bookplate is particularly well designed, or sufficiently grotesque and unusual, or if it belonged to a famous or significant person, then it probably adds to the desirability of the book.

Content

Content is a fairly

straight forward matter to consider in book collecting. By content, I

mean the text and the illustrations (if any).

Text

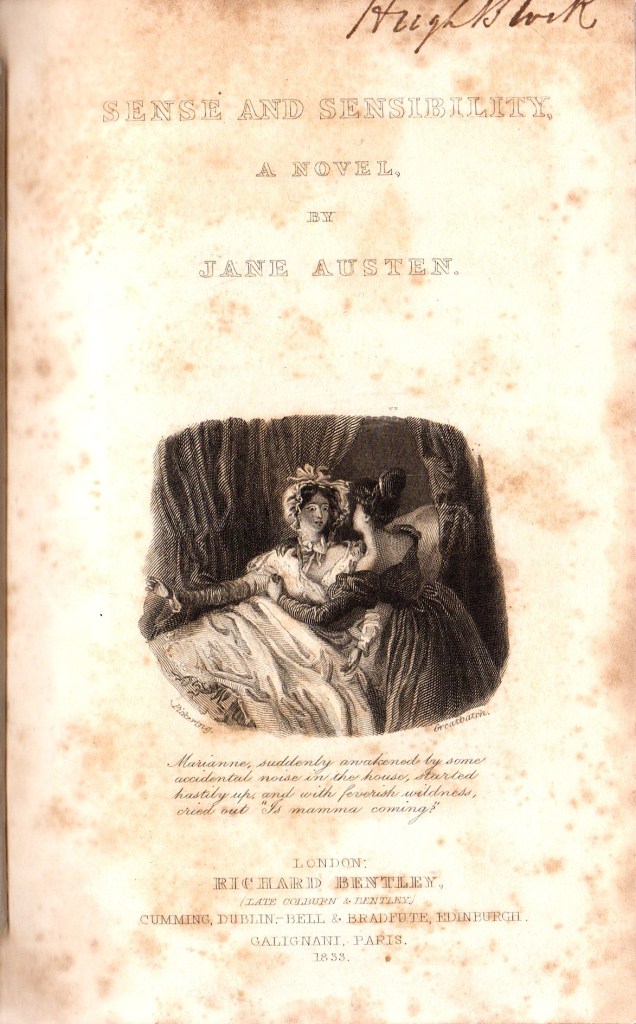

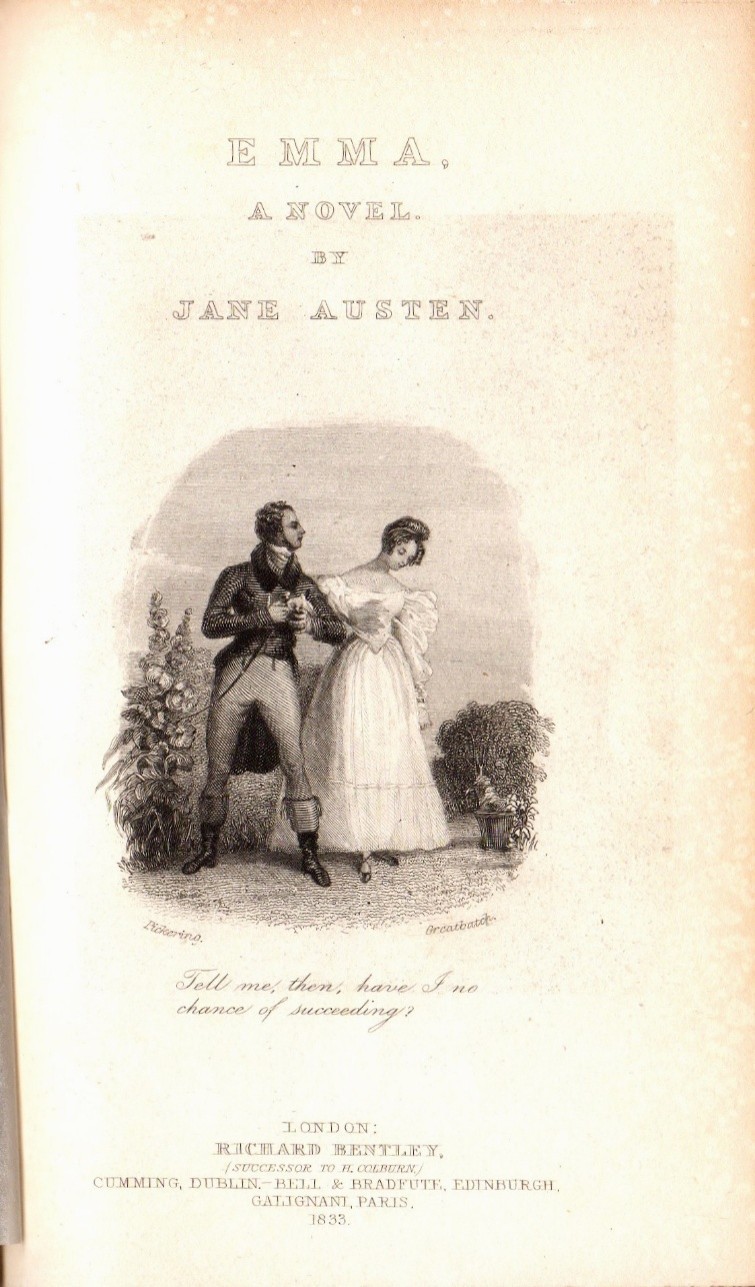

If the book is a classic or prize winning or ground-breaking work, then it will be intrinsically more desirable. For most authors, there are one or a few stand-out titles which are the most collected. For George Orwell for instance, I think that everyone would identify “Animal Farm” and “1984” as his most desirable books. On the other hand, almost anything by Charles Dickens, Jane Austen or the Brontes would be very desirable.

The nature of the text is also important. Most collectors prefer the detective fiction of Dorothy Sayers to her religious works; similarly, the Narnia books and the three space fiction novels of CS Lewis are more collected than his academic or religious books. Most collectors would rather have Rider Haggard’s “King Solomon’s Mines” or “She”, rather than his scarce first book, “Cetewayo and his White Neighbours”, or his later books on farming.

Charles Darwin’s “On The Origin of Species” probably is a unique book in its profound impact on human ideas and life. Any copy of this text has some interest to collectors, from the first edition of 1859 down to the many modern reprints that have appeared since.

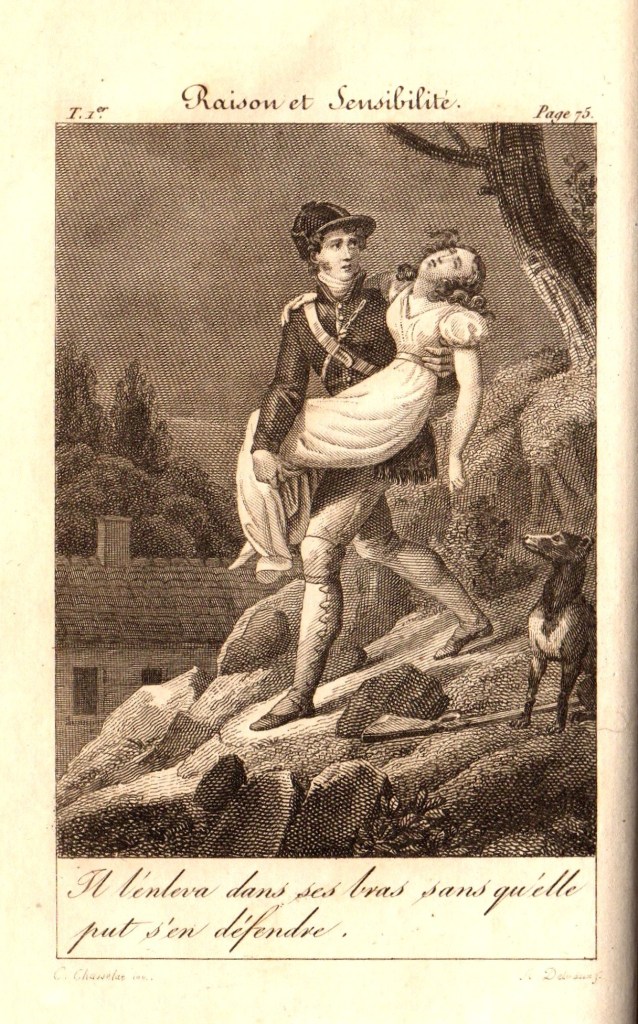

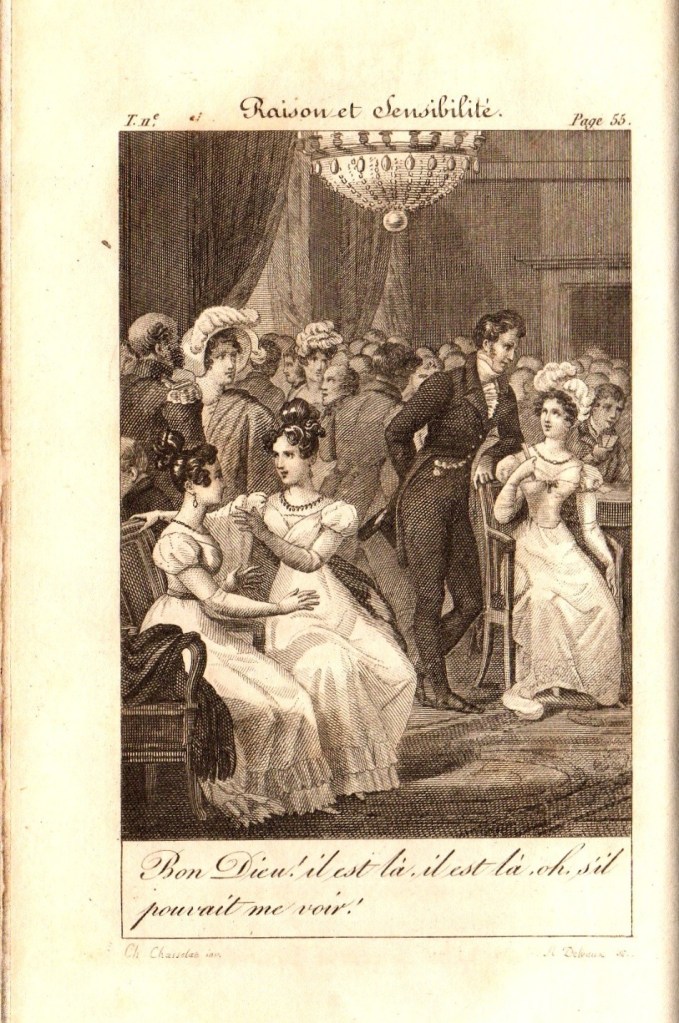

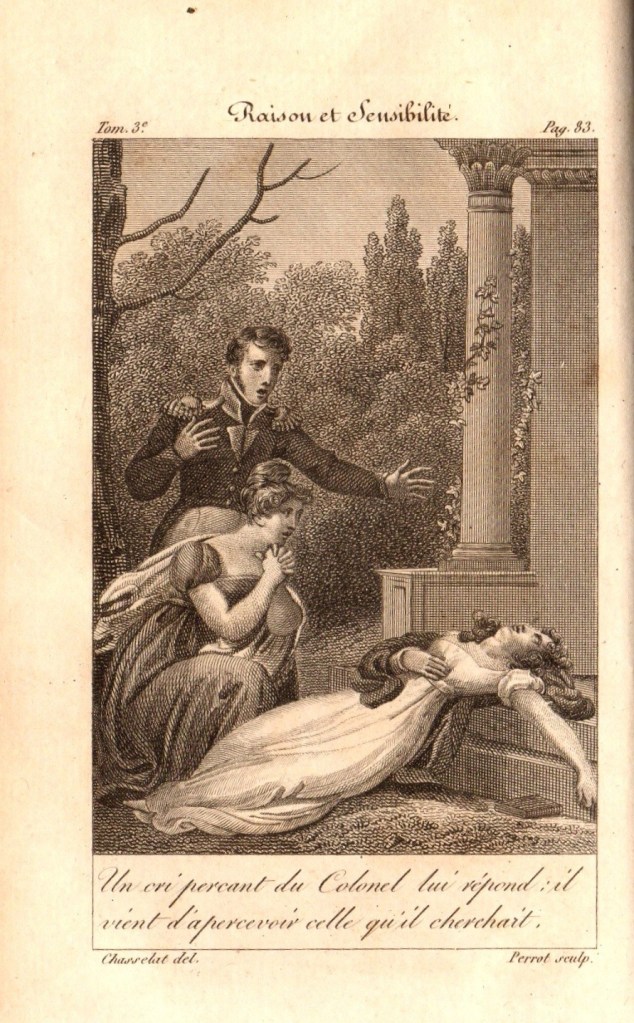

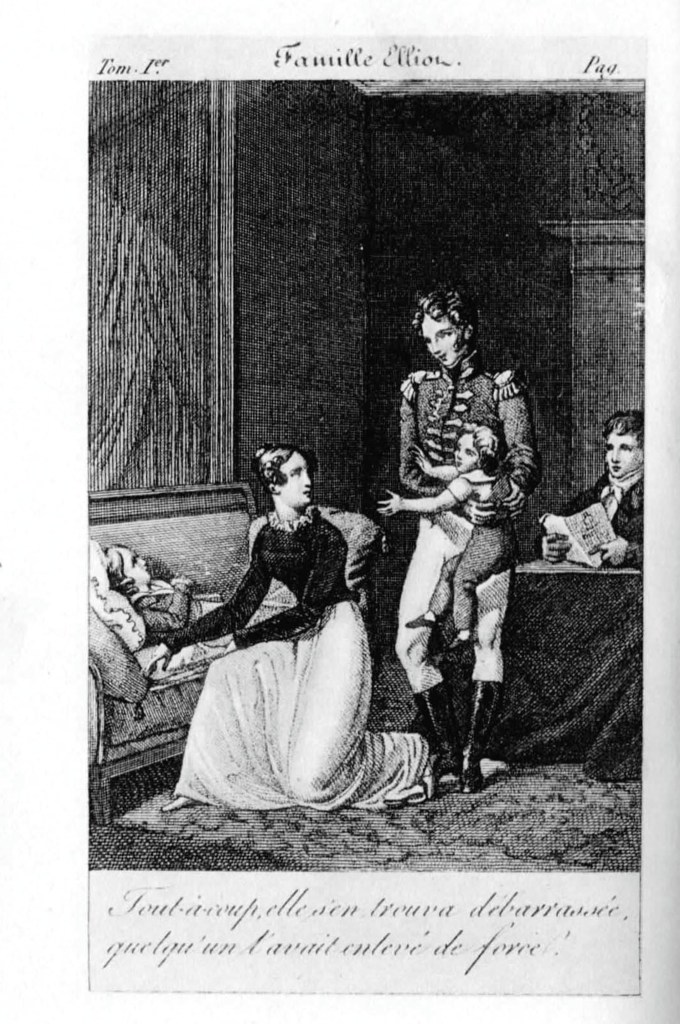

Illustration

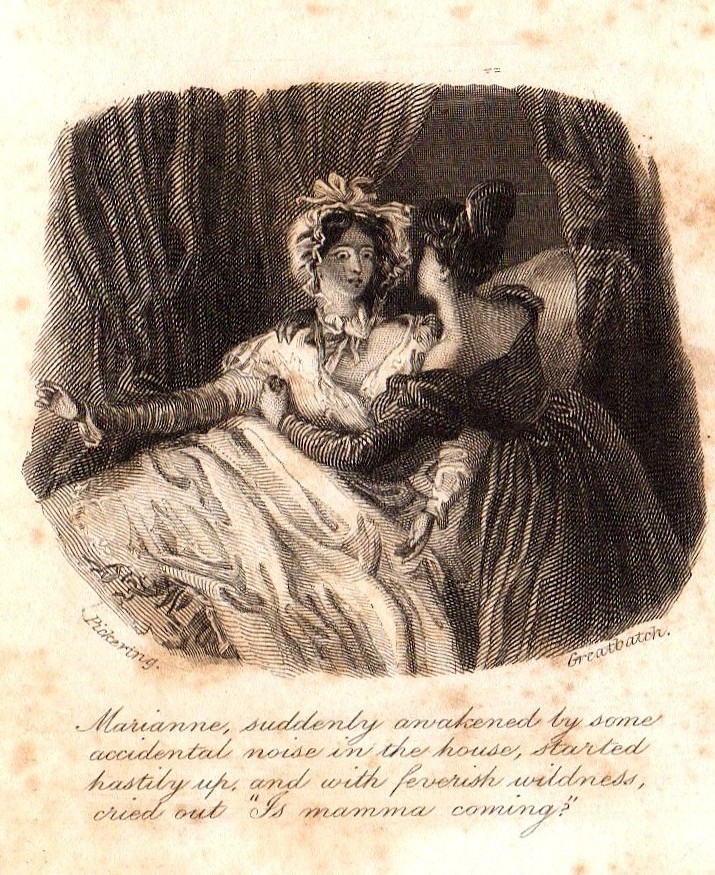

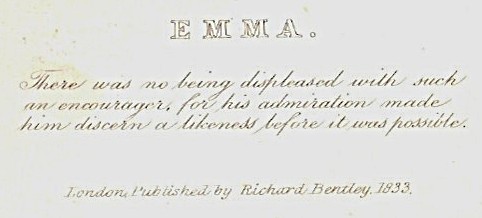

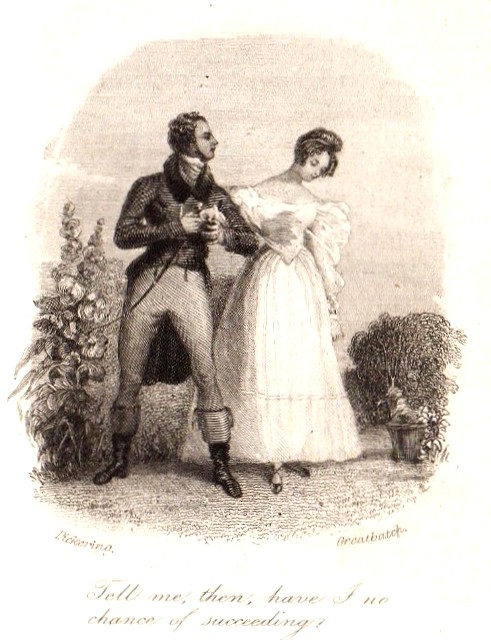

Illustrated books also have a content collectibility over and above the written text. Many books have been published in un-illustrated first editions, which, after the book’s success as text has been established, are re-issued in lavishly illustrated and finely bound editions that many collectors crave. For collectors of English books, the golden age of book illustration is generally held to be the period 1875 to 1914.

I personally have collected editions of the Alice books of Lewis Carroll illustrated by many illustrators over the last hundred years or so. Although the original illustrations in the first editions of 1865 and 1871 were famously and iconically created by Sir John Tenniel, many famous illustrators have produced wonderful illustrations since then. In a future blog, I will discuss these books and illustrations.

Rarity

Rarity is determined by a number of factors. Age is certainly one, and although old books are not necessarily highly collectible, there is no doubt that age will have an effect on survival of any book, and so will affect rarity.

The size of an edition is also a key factor. The first edition of the first book by an unknown author is usually published in very small numbers, as the publishers want to limit their risk of losses. If the book is successful, then the publisher can print more copies and issue new editions, according to the book’s popularity. Nowadays, if a film is made of the book, new editions are published to take advantage of the marketing of the film.

An interesting recent example of the first book phenomenon is offered by the Harry Potter books of J K Rowling. The first book in the series, “Harry Potter and the Philosopher’s stone” (1997), as the first book by an unknown author, was published in a standard small first UK hardback edition of 500 copies in laminated boards, along with a paperback edition of a few thousand books. 300 of the 500 hardbacks were sold to the English School Library system, where they will have been read to destruction, leaving only 200 copies for book collectors. These now attract massive prices, around $50,000, in specialist book auctions. Copies signed by Rowling will cost even more.

The second book “Harry Potter and the Chamber of Secrets” (1998) and third book “Harry Potter and the Prisoner of Azkaban” (1999) were both published in UK hardback first editions of about 10,000 copies each. These are also highly collected and quite expensive, generally costing around $1000 , depending on condition and issue, rising to $7500 if they are signed by the author.

By the fourth book “Harry Potter and the Goblet of Fire“, (2000), the Harry Potter phenomenon had well and truly taken off. The first UK hardback edition numbered one million books! Although these are still collectible, they are easy to find, and not very expensive. The same is true for the last three books, published in massive first editions and therefore relatively common and easy to find. Interestingly, the first UK hardback edition of the first James bond book “Casino Royale” (1953) is also very rare and highly desirable, due to a small edition being printed (about 4500 books), of which half went to the UK Public Library Service and were read to destruction… a similar story to the first Harry Potter book.

In a parallel story, the first edition of Charles Darwin’s “On the Origin of Species“, was published by John Murray on 24th November 1859 in a first edition of only 1250 copies of which 1170 copies were available for sale. 500 of these were purchased by Mudie’s Library and all of the rest were pre-sold before publication, mainly due to the intense interest in the subject at the time. Many ended up in institutional libraries, so that the number of copies in private hands, which are those that tend to become available to the rare book trade, was very limited. A first edition can still sometimes be offered for sale in 2015, but it will cost around $250,000. A copy famously sold for around this price on the 150th anniversary of its publication in 2009.

Condition

Condition is the final factor that I will consider here. Book collectors want the best possible condition of any book that they want to collect. The book should ideally be complete, in the original binding and dust jacket, with no marks, tears, scribblings, sticky tape scars, water or light damage, library detritus or stains. It should ideally look like a brand new copy of the book on the day of issue, before it has been read.

This Ideal is not always attainable, and so the more scarce and desirable a book is, the more collectors will compromise on condition. Small stains and small repaired tears and creases in the dust jacket are often acceptable. All illustrations must be present in an illustrated book, but looseness of tipped-in illustrations can be acceptable and can be easily repaired. The title page must be present and all of the text must be present, but some people will accept the loss or disfigurement of the free front end paper (the blank page often found at the front of a book, before the title page). Looseness or defects in the binding, usually found in the “gutters”, the region where the pages are attached to the boards, are grudgingly acceptable to most, and the absence of tissue guards, the protective tissues for illustrations, particularly frontispieces are common and also generally acceptable.

Foxing, the appearance of brown stains due to a mould within the paper is common and also acceptable if not too severe. (A well known comical book on book collecting, illustrated by Ronald Searle, is famously titled “Slightly Foxed, but Still Desirable”, echoing the description often given in book dealer’s catalogues.)

Not surprisingly, the older a book is, the more damaged and worse for wear it is likely to be. Most collectors will accept this and take a pragmatic view of this issue. Thus I expect a much higher standard for my Terry Pratchett first editions, all of which were published after 1983, than my Charles Dickens first editions, all of which were published between 1834 and 1870.