Richard Bentley, London, Gilson D2

The first edition of Emma, the fourth novel to be published by Jane Austen, was published in 3 volumes in December 1815 by John Murray. Like all of the first editions of Austen it was not illustrated. It was the first Austen title published by John Murray, following some dissatisfaction with Thomas Egerton, who had published the first three Austen novels. The first edition of Emma was issued as 2000 copies, which all sold within one year of publication. Following Jane Austen’s death on 18th July 1817, John Murray resisted efforts by the Austen family, notably the author’s brother Henry and sister Cassandra, to publish a second edition of Emma.

Richard Bentley (1794-1871) had been born into a distinguished family of three generations of printers and publishers. After initially working in partnership with his brother Samuel as “S. and R. Bentley” for ten years, Richard formed a new partnership with Henry Colburn in 1829. Colburn and Bentley had started to publish a series of cheap, illustrated reprints of English novels as “Colburn and Bentley’s Standard Novels” in 1831. They offered reprints of novels in a single volume for six shillings. Each volume had two illustrations, an engraved frontispiece illustration and an engraved title page which had a smaller “vignette” illustration. The first novel in the series was The Pilot by James Fennimore Cooper, published in February 1831 and the highlight of the early titles was Frankenstein by Mary Shelley published on 31st October 1831. After an acrimonious dissolution of the partnership in mid-1832, by which point 19 Standard Novels had been printed and published, Richard Bentley continued with his own series of “Standard Novels”.

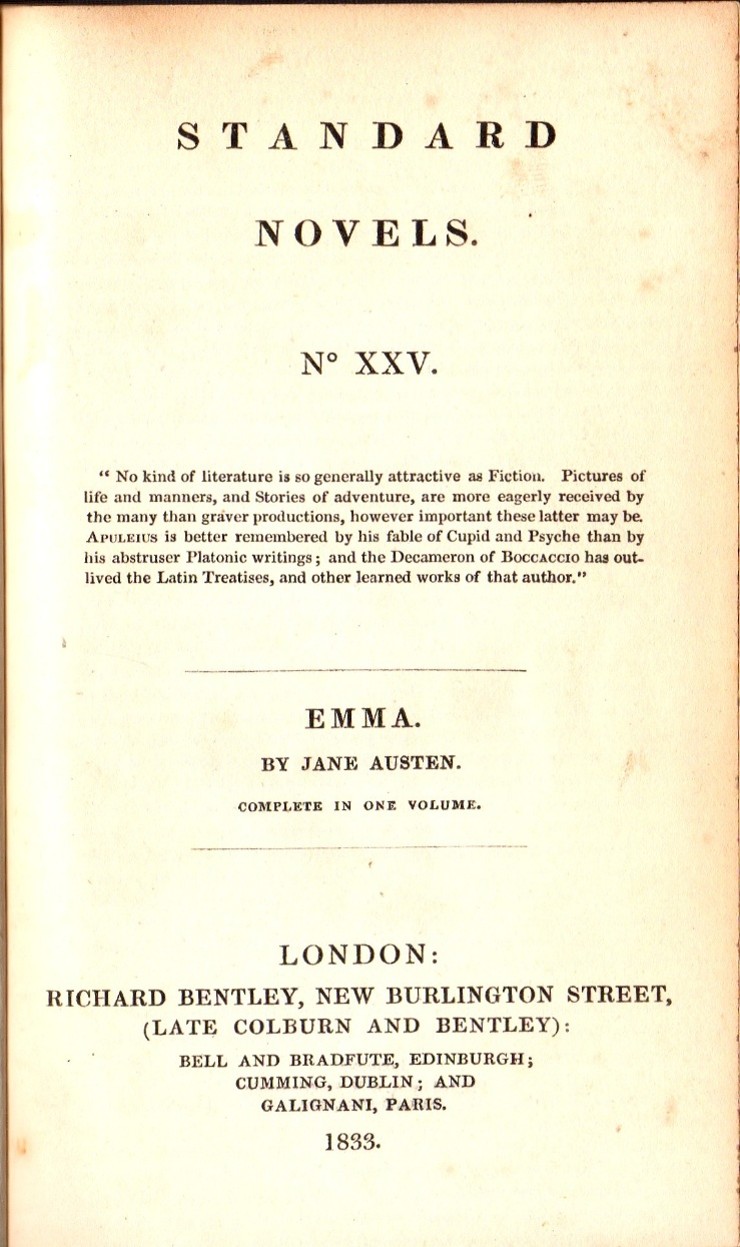

Emma, along with the other five novels of Jane Austen that had been published between 1811 and 1817, did not appear in a new English edition until Richard Bentley decided to reprint all of the Austen novels as “Standard Novels” in 1832. Emma was published by Richard Bentley on 27th February 1833, following his purchase of the Austen copyrights from Cassandra Austen via Henry Austen. Emma was numbered “XXV” (25 ) in the Standard Novel series. It was the second edition of Emma to be published in the UK, the first single volume edition, the first edition to have any illustrations and the first to have Jane Austen’s name as author on the title page(s). It was the second of Austen’s novels to be published by Bentley, following Sense and Sensibility (Gilson D1), which was published as Standard Novel number XXIII (23) on 28th December 1932, although it was dated 1833. Standard Novel XXIV (24) was a translation of Madame de Stael’s Corinne, which appeared on February 1st 1833.

The format of Bentley’s Standard Novels was indeed standardised, so that each volume had a “series title page”, which identified it as a part of the Bentley’s Standard Novels series with a date of publication and a series number, a full page engraved frontispiece, an engraved title page, normally with an engraved date, and a letterpress or printed title page which had the title, authors name, Bentley’s name and address and a publication date. These four pages for first Bentley edition of Emma are shown in figure 1.

Figure 1. Series Title, Frontispiece, Engraved Title and Letterpress Title pages

Bentley published Emma in the same volume and chapter format as the original three volume first edition published by John Murray in December 1815. The novel starts with Emma | Volume the First | Chapter I. on page 1, and finishes Volume the First with the end of Chapter XVIII (18) on page 134 with the line “End of the First Volume”. Volume the Second begins with Chapter I of the second volume on page 135 and ends on page 279 at the end of Chapter XVIII (19) of the second volume, with the line “End of the Second Volume”. Volume the Third then begins on page 280 and the novel ends on page 435 with the last page of Chapter XIX (19) of Volume three with the simple words “The End”. By maintaining the volume and chapter structure of the first edition, Bentley has ensured that any sentence from any chapter of any book will be found in the same chapter and book in the Bentley edition as it was in the Murray first edition.

The book ends with the printer’s colophon on the verso of page 435. It reads “London: Printed by A. & R, Spottiswoode, New-street-Square.” on three lines. The only page missing from the Bentley edition of Emma is the dedication page that was included in the first edition of 1815, where Jane Austen dedicated Emma to the Prince Regent with these words: “To His Royal Highness, The Prince Regent, this work is, by His Royal Highness’s permission, most respectfully dedicated, by His Royal Highness’s dutiful and obedient humble servant, The Author.” It is not clear why Bentley chose not to include the dedication. It may be due to the fact that the Bentley edition of Emma was first published in 1833, in the reign of King William IV, younger brother and successor to the late, former Prince Regent, who had eventually reigned in his own right from 1820 to 1830 as King George IV. Perhaps respect to the present king outweighed respect to his predecessor.

Illustrations in Bentley’s 1833 edition of Emma

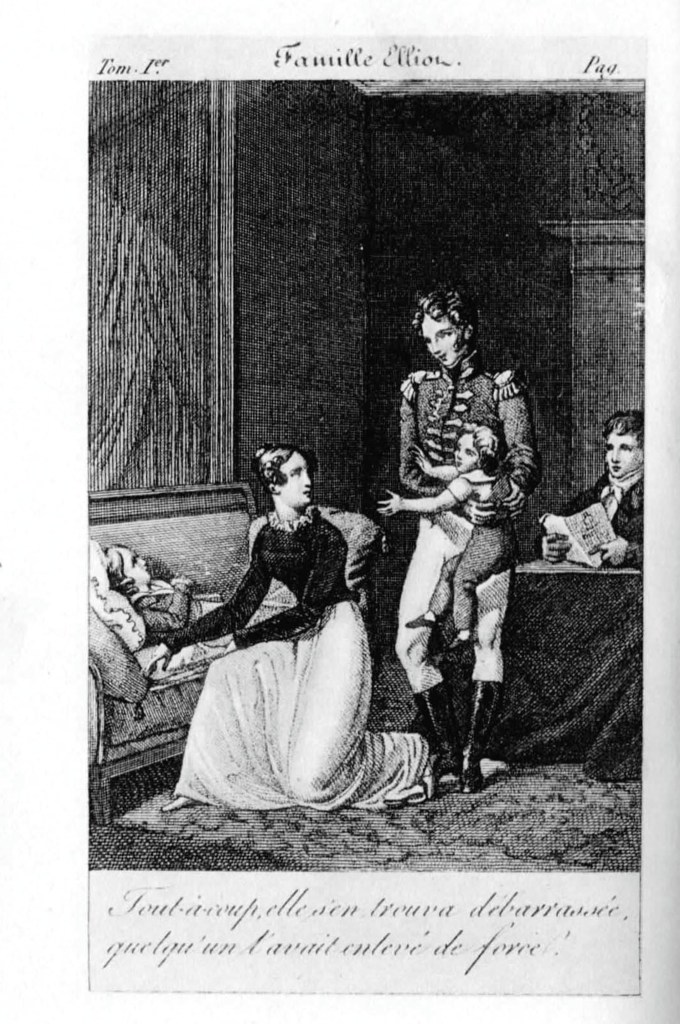

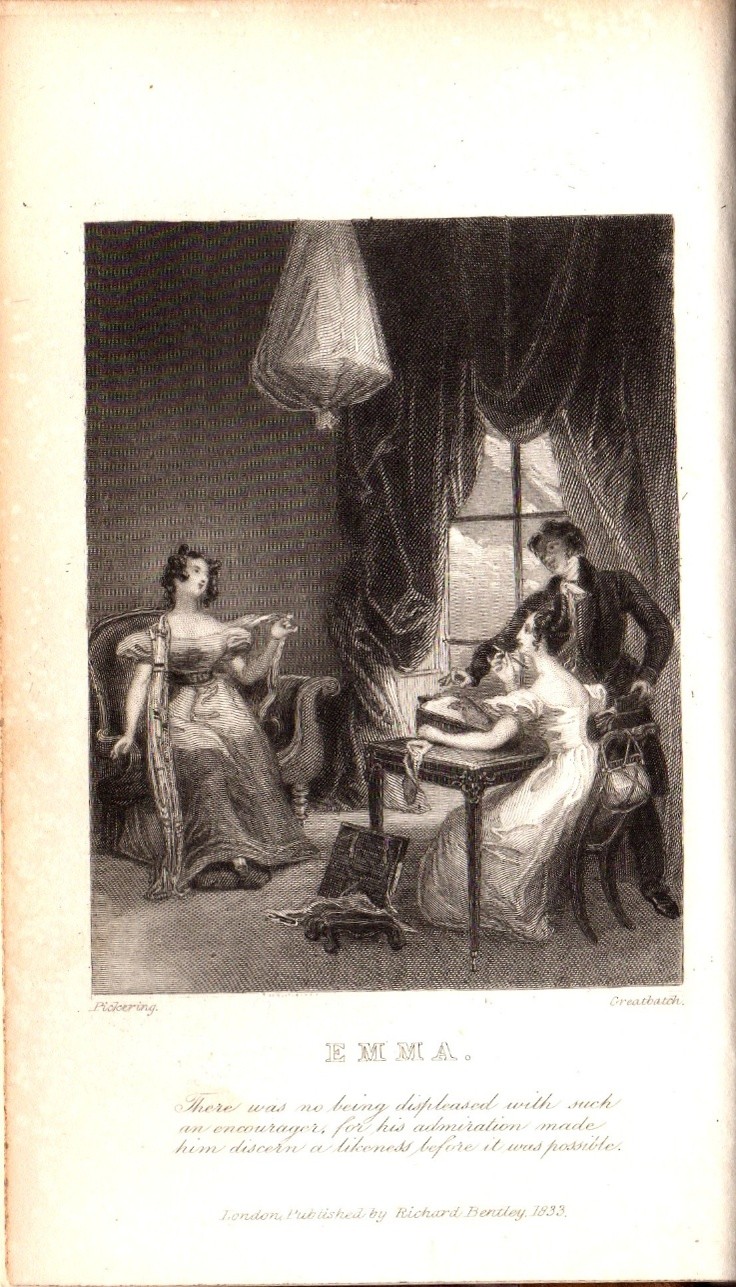

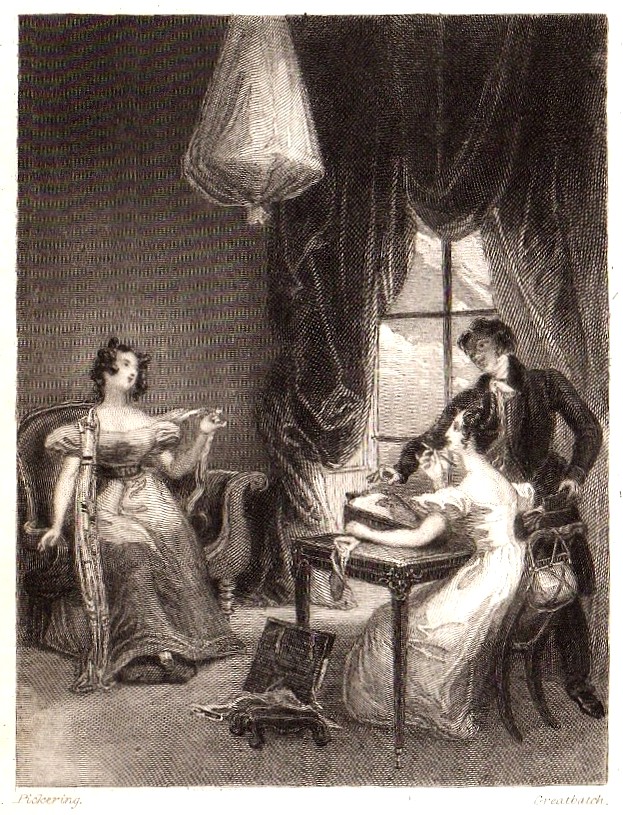

The two illustrations in this edition of Emma were drawn by Ferdinand Pickering (1810-1889) and engraved on wood by William Greatbatch (1802-1872). The identity of the artist had been uncertain for many years. The illustrations in Emma are clearly signed “Pickering”, which led David Gilson to suggest that they were by George Pickering (ca 1794-1857). However, other illustrations in the Standard Novel series that have many similarities of style to those in Emma are clearly signed “F. Pickering”, which has led to the corrected identification of Ferdinand Pickering as the artist. An enlarged version of the frontispiece is shown in Figure 2.

Figure 2. Frontispiece of Emma from Gilson D2.

The name “Pickering” can be clearly seen at the bottom left of the image and “Greatbatch” at the bottom right. The picture depicts Emma Woodhouse drawing a portrait of her friend Harriet Smith, while Mr. Elton is playing very close attention to Emma. The style of the costumes is from the 1830s rather than being correct for the late 18th century to Regency period. The legend of the frontispiece is shown below as Figure 3.

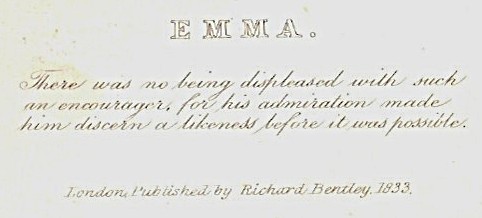

Figure 3. Text below the frontispiece of Emma

The text reads “There was no being displeased with such an encourager, for his admiration made him discern a likeness before it was possible.” It is a direct quotation from Chapter 6 of Emma. Mr. Elton is lavishing praise on Emma, who he greatly admires, despite Emma’s attempts to deflect his attentions to Harriet. The final line in a smaller font reads “London, Published by Richard Bentley. 1833.” This is the publisher asserting his ownership of the copyright of the image, which he commissioned from Pickering and Greatbatch.

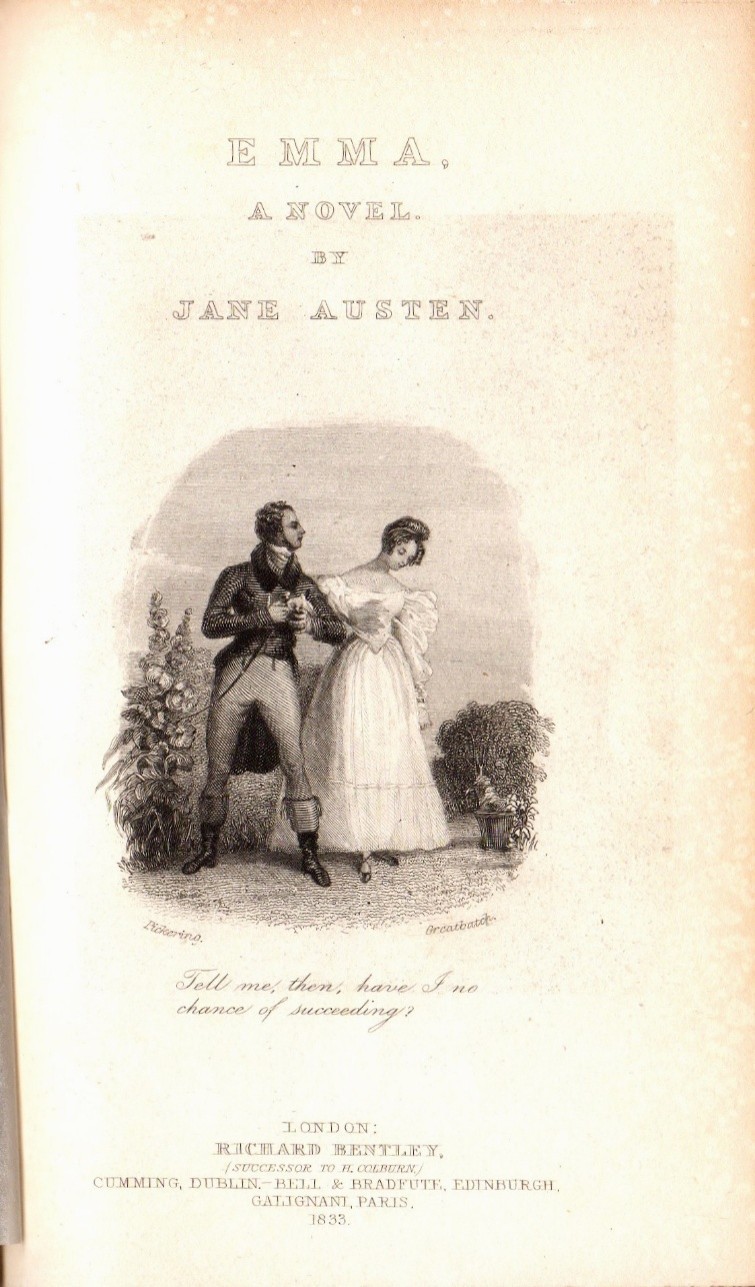

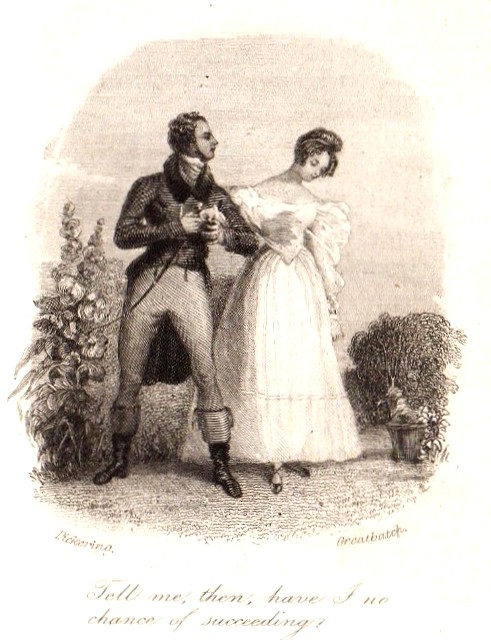

The engraved title page, together with an enlarged picture of the illustration, are shown below in Figure 4.

Figure 4. Engraved title page and vignette image from Emma

The engraved title page announces at the top that this is “EMMA. | A NOVEL. | BY | JANE AUSTEN.”. At the bottom of the page the publishers details are given thus: LONDON | RICHARD BENTLEY | (SUCESSOR TO H. COLBURN) | CUMMING, DUBLIN BELL & BRADFUTE, EDINBURGH | GALIGNANI, PARIS | 1833 . In the vignette, in the right hand panel, we see Emma out walking with Mr. Knightley, who has just declared his love for her. He then asks her “Tell me, then, have I no chance of succeeding?” which is the text below the image. This is taken directly from Chapter 49 of Emma. You can also see the names of Pickering and Greatbatch on the left and right lower corners of the image.

Reprints of the Bentley 1833 edition of Emma (Gilson D7)

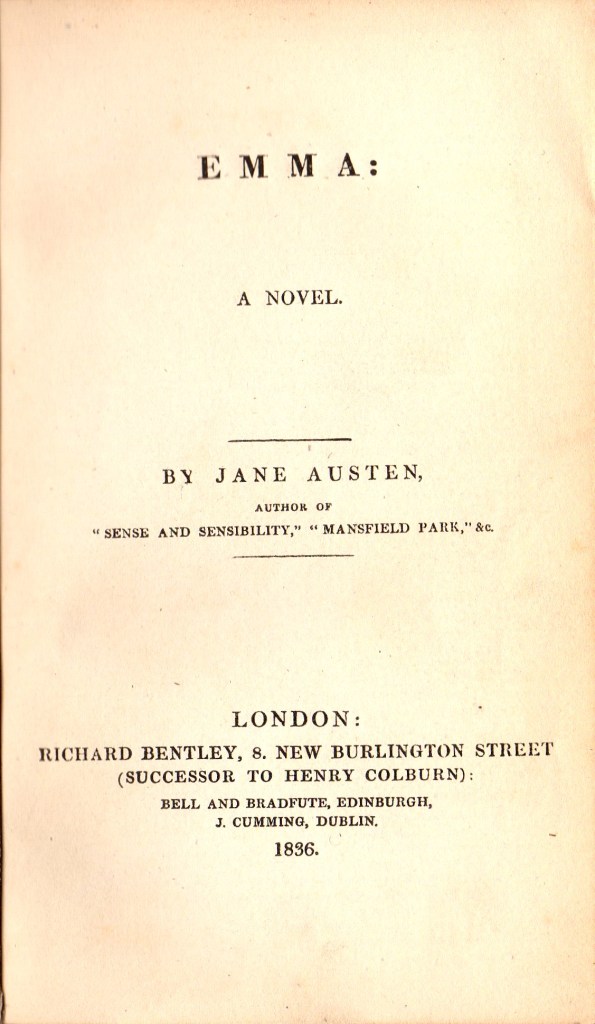

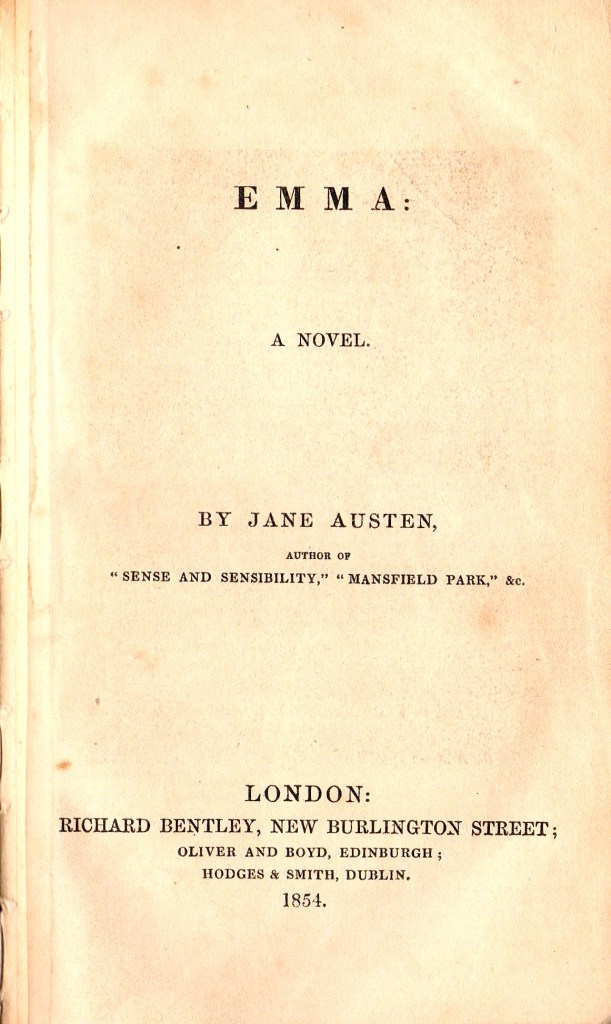

Bentley’s edition of Emma was reprinted several times in the subsequent 35 years. Stereotype plates were created and used for reprints of Emma (Gilson D2) for the Standard Novels series that were published in 1836, 1841, 1851, and 1854. Emma was also reprinted as a part of five volume sets of “The Novels of Miss Austen” that were published in 1833, 1853, 1856 and 1866. All of the reprinted Bentley editions of the Austen novels were designated D7 by David Gilson. I have copies of the 1833, 1836 and 1854 issues of Emma and of the 1856 five volume set of the six novels. In Figure 5 below, I show the printed title pages for my Emma editions of 1836, 1854 and 1856. As well as having a different date from the 1833 edition, these are differences in the page layout, Bentley’s address and the Edinburgh and Dublin publisher’s details.

Figure 5. Emma Title pages from Gilson D7 editions of 1836, 1854 and 1856

All these three reprinted editions also contain the original engraved frontispiece from 1833. The 1836 and 1856 editions also contain the engraved title page that was first published in the 1833 edition, shown in Figure 1 above. The engraved pages all still show the date 1833.

The two Standard Novel reprints of 1836 and 1854 do not have a series title page, whereas the 1856 reprint from The Novels of Miss Austen set has a half title which just bears the single word “EMMA”. The page and chapter layout for the three reprinted editions are all identical to that of the 1833 first Bentley edition. However, the printers colophons on the verso of page 435 are all different from the 1833 edition. All editions have “London:” on the first line and “New-street-Square” on the third line but are all different in the second line. These are shown below.

- 1833 edition: Printed by A.& R. Spottiswoode,

- 1836 edition: Printed by A. Spotiswoode,

- 1854 edition: A. & G. A. Spottiswoode,

- 1856 edition: Printed by Spottiswoode and Co.,

Provenance of my Bentley Emma edition of 1854

In Figure 6 below, the front endpapers of my 1854 Bentley edition of Emma are shown. They show the provenance of this book in more recent years.

Figure 6. Front endpapers of my 1854 copy of Emma (Gilson D7)

The most obvious and prominent feature in Figure 6 is the bookplate of David John Gilson on the front pastedown. This is the Gilson who compiled the standard bibliography of Jane Austen and its is an absolute privilege for me to have this copy in my Austen collection. Gilson actually mentions this copy on page 229 of the Oak Knoll Press second edition of A Bibliography of Jane Austen. Above the Gilson bookplate there is an inscription in pencil which reads: ” D7: 1854 | Given to me by | David G | 3/8/85″. This was written by Gilson’s friend John Jordan, whose bookplate is on the lower right of the free front endpaper. The two other inscriptions are: “T. Lindsay, 1914″, doubtless a previous owner of the book, and the lower line which reads ” Rebound: Ferney-Voltaire; 1953″. The book is bound in an obviously 20th century ivory textured cloth binding.

Ferney-Voltaire is a small commune of around 10,000 in south-eastern France, close to the Swiss border. It was the residence of Voltaire from 1758-1778 and his Chateau can still be visited there. As well as the Voltaire museum in the Chateau Voltaire, there is a small workshop and museum of printing and bookbinding in Ferney-Voltaire called Atelier du Livre. It is currently run by an Englishman, Andrew Brown. This may be where the 1854 Emma was rebound in 1953, by a previous owner.

Return to the Index page for Illustrated Editions of Jane Austen.