Category: Uncategorized

1793 Castle of Wolfenbach: Emily Parsons

1793 Castle of Wolfenbach: Emily Parsons

Return to the Gothic Novel list

1786 Vathek: William Beckford

1786 Vathek: William Beckford

William Beckford was perhaps best known for building an expensive Gothic folly, Fonthill Abbey, which collapsed spectacularly in 1825, and Lansdown Tower, now known as Beckford’s Tower, which is still standing in Bath.

1778 The Old English Baron: Clara Reeve

1778 The Old English Baron: Clara Reeve

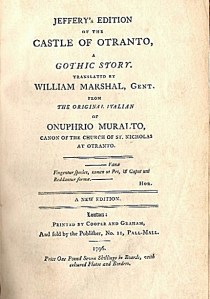

1764 The Castle of Otranto: Horace Walpole

1764 The Castle of Otranto: Horace Walpole

My Twenty-one Best Gothic Novels

My Twenty-one Best Gothic Novels

The Gothic novel has a key place in the history of English literature from the mid 18th century until today. Below is a list of my twenty-one most desirable examples of Gothic Literature from a book collector’s perspective. In this article, I will briefly discuss elements of the publication history of each of the twenty-one works that I have chosen. I will also nominate which edition I would select as the most desirable to have in my Gothic Library. Although to most book collectors, the first edition of any book is often the most desirable, that is not necessarily the case, and I will try to explain here why I think each “most desirable” edition that I have nominated has its special appeal. The choice is of course entirely personal.

Melbourne Rare Book Week 2017

Melbourne Rare Book Week 2017 will be held from Friday 30th June until Sunday 9th July inclusive.

This will be the sixth year for this festival of all things book and printing, and as usual will culminate in the Melbourne Rare Book Fair at Wilson Hall at The University of Melbourne from the 7th until the 9th of July 2017.

More than 50 events, all free to the public, will be held during Melbourne Rare Book Week and the full program will ne available from Monday 22nd May 2017.

From Monday 22nd May 2017, you can log on to the Melbourne Rare Book Week 2017 web site to see the program and to book for the events that you wish to attend.

You will find Melbourne Rare Book Week 2017 at

and the Melbourne Rare Book Fair at

Among the highlights of Melbourne Rare Book Week will be an exhibition dedicated to Jane Austen called

which will run from June 5th until July 23rd inclusively at The Library at the Dock, Victoria Harbour, Docklands.

More information on both Rare Book Week and the exhibition will be available here shortly.

The Books of Jane Austen

The Books of Jane Austen: Part 1

18th July 2017 marks the 200th anniversary of the death of Jane Austen. We now take for granted the almost universal popularity of the six mature novels and have a seemingly insatiable appetite for film and TV re-interpretations of the plots and characters. It is easy to forget that the popularity of the books was not instant and that for a long period of time, following the author’s death, they were actually out of print. This is the first of a series of postings about the books of Jane Austen.

The early writing history of Jane Austen

Jane Austen was born on 16th December 1775, at the vicarage at Steventon in Hampshire to the local rector, George Austen and his wife Cassandra Austen nee Leigh. She had six brothers and one sister, named Cassandra like her mother, who remained her closest friend and confidant during her lifetime.

Jane Austen started writing for her own and her family’s amusement at about the age of 12. Later in life, she made fair copies of these early writings, now called her ‘Juvenalia,’ in three notebooks that she labelled with mock pomposity ‘Volume the First’, Volume the Second’ and ‘Volume the Third.’ These three volumes were eventually published many years after her death.

In around 1793, at the age of 18, Jane, or Miss Jane Austen as she would have been known by her friends and neighbours, began to write more mature and longer works with a view to eventual publication. Between 1793 and 1795, she wrote Lady Susan, a short novel written in the form of letters, which we call an ‘epistolary’ novel. She then started a longer novel that she called ‘Elinor and Marianne’, also as an epistolary novel, that was finished by 1796. She then embarked on ‘First Impressions’, another long novel that she completed in mid 1797. After this had been read to the family, and much enjoyed, her father wrote to the publisher Thomas Cadell in London to try to interest him in publishing ‘First Impressions’. The letter was returned marked “Declined by return of post.”

From late 1797 until mid 1798, Miss Jane Austen reworked ‘Elinor and Marianne’, changing it from an epistolary novel to a plain narrative form. At some time in mid 1798, she embarked on a gothic romance that she called ‘Susan’, that she completed by mid 1799. Her brother Henry Austen sent the manuscript of ‘Susan’ to another London publisher, Benjamin Crosby, in 1803. Crosby paid ten pounds for the copyright and promised to publish the novel, but nothing happened.

George Austen retired as the Rector of Steventon in December 1800 and moved his family his wife and two daughters to Bath. The Austen family lived in Bath from 1801 until 1805 when George Austen died. Miss Jane Austen wrote very little during that period and was not happy to have been moved from Steventon. For the next four years, after the death of her father, the three Austen women led a peripatetic, unsettled and uncertain life, until Miss Jane Austen’s brother, Edward Austen Knight, who had been adopted by a rich relative and had inherited large estates, offered his mother and two sisters the use of a cottage at Chawton in Hampshire, that was part of one of his estates, Chawton House. The three women moved into Chawton Cottage on 7th July 1809, and Miss Jane Austen resumed her interrupted writing life.

Jane Austen: The first published text

We know that Miss Jane Austen revised the text of ‘Elinor and Marianne’ during her first year at Chawton.

In early 1811, acting as his sister’s literary agent, Henry Austen, now living in London and working as a banker, offered the revised manuscript of ‘Elinor and Marianne’, now retitled as ‘Sense and Sensibility’ to the London publisher Thomas Egerton, Egerton advertised himself as ‘Thomas Egerton of Whitehall’, but his offices were actually around the corner from Whitehall in St. Martin’s Lane.

Miss Jane Austen retained the copyright to ‘Sense and Sensibility’, and agreed to pay for the printing and publishing expenses of the book. A first edition of between 750 and 1000 copies was published by Egerton in October 1811. The title page famously reads:

Interesting books of Yesteryear: Invasion 1940 by Peter Fleming

This is the first of a series of blogs on interesting, out of print and hard to find books. They will mostly be more than 20 years after their first publication.

“Invasion 1940” by Peter Fleming

‘Invasion 1940‘ by Peter Fleming was published by Rupert Hart-Davis in London in 1957. An American edition of the book was published in the same year by Simon and Schuster as ‘Operation Sea Lion.’ The book is an account of the invasion plans that Adolf Hitler and the German military high command prepared for an Invasion of the United Kingdom following the fall of France in June 1940. The book also documents British preparedness, or the lack thereof. This was the first published account of these events, predating the Official War History account, Basil Collier’s “The Defense of the United Kingdom” by five years.Historical background

The order to prepare the first plans for a cross-channel invasion was issued on 15th November 1939 by High Admiral Erich Raeder, the senior commander of the German navy. At the Nurenberg War Crimes trials, Admiral Raeder said that he did this as a precautionary measure, in case Hitler suddenly demanded such a plan from him.

The first discussion on the topic between Hitler and Raeder was initiated by Raeder on 21st May 1940, during the German army’s successful armoured thrust into France, which had commenced on 10th May 1940, and just before the successful British evacuation of some 338,000 troops from Dunkirk, which took place between the 27th May and 4th June1940. France collapsed and surrendered on 25th June 1940. The outcome of the discussion between Raeder and Hitler was the issuing of Directive No. 16 on 16th July 1940 by Hitler. The beginning of Directive No 16 is quoted by Peter Fleming thus:

As England, in spite of the hopelessness of her military position, has so far shown herself unwilling to come to any compromise. I have decided to begin to prepare for, and if necessary to carry out, an invasion of England.This operation is dictated by the necessity of eliminating Great Britain as a base from which the war against Germany can be fought, and if necessary the island will be occupied.

from Adolph Hitler, Directive No. 16, 16th July 1940

I have therefore issued the following orders…

The invasion plan was given the code name Operation Sea Lion, ‘Unternehmen Seelöwe’.

An outline of the book

Fleming gives many details of the plans for Operation Sea Lion in the book and documents much of the information he uses. He gives many logistical as well as strategic and tactical details of the invasion plans. In two fascinating chapters, he explores what the German military intelligence knew of the British military forces, and vice versa. He also gives an excellent account of the English response which went from apathy through denial to preparedness and resolve, catalysed by the crucial change of leadership from Chamberlain to Churchill on 10th May 1940.

He start with a very brief account of the opening military actions of World War II in Poland, Norway, Belgium and Holland and finally France. This approach somewhat assumes that the reader is already familiar enough with this (to the author) very recent history. While this attitude was probably true for his readership in 1957, I doubt that this is so today.

Fleming does give the reader much more detail of the attitudes of the English up to May 1940, and includes this wonderfully complacent quotation from Britain’s then leading military historian:

England…is…more secure than ever before against invasion…. There is sound cause for discounting the danger of invasion.

from ‘The Defence of Britain’ by Basil Liddell-Hart. July 1939

A fairly full and satisfying account of the naval and air situations is presented and a full and detailed account of the crucial failure of the Luftwaffe to defeat the RAF in the Battle of Britain is also very well presented by Fleming. There is quite a lot of speculation about how seriously the Germans really contemplated an invasion, which, while planned as if it was an extension of a military crossing of a large river while under enemy fire, was clearly going to require an operation of a much larger order of magnitude. No modern amphibious operation on this scale had ever been contemplated, involving 9 army divisions in the first wave and requiring close co-operation of land sea and air forces.

It does seem that Hitler was hoping for a British capitulation or, at least, a willingness to negotiate a position of armed neutrality, while agreeing not to interfere with the German military activities in continental Europe, particularly looking to the East. Fleming suggests that, probably, no-one in the senior German military leadership was really keen to commit to the scheme due to its inherent riskiness. From the outset of the planning, the following prerequisites were identified:

- Elimination or sealing off Royal Navy forces from the landing and approach areas.

- Elimination of the Royal Air Force.

- Destruction of all Royal Navy units in the coastal zone.

- Prevention of British submarine action against the landing fleet.

Fleming describes how the German Navy was very concerned by their large losses after the campaign in Norway in 1939 and could not neutralise the Royal Navy. This, coupled with the Luftwaffe’s failure to eliminate the RAF, left all four of the pre-requisites for invasion unmet.

Ultimately, the invasion plan was formally abandoned on 17th September 1940. Interestingly, Fleming tells us that, although Hitler joked about the invasion in a speech given on the 4th September, he had probably already decided that the invasion was impossible. Fleming also reveals that some of the units that, were earmarked for the invasion of Britain, were not released for other action or theatres of war until the spring of 1942.

The book also gives an interesting account of the German plans for the governance of a successfully defeated and occupied Britain, including a reproduction of four pages of the famous ‘Black List’ of leading Britons to be ‘neutralised.’

The book is illustrated by contemporary black and white full page photographs, that are of mainly very high quality, and also has many vignettes of contemporary cartoons which underscore or lampoon the history and politics of the time.

I can thoroughly recommend this book as a well written interesting insight into what might have been, two generations ago. Fleming’s writing style is lively and relatively undated.

About the Author

Peter Fleming (1907-1971) was one of four sons born to a World War I hero and victim, Colonel Valentine Fleming MC, MP (1882-1917). Peter Fleming was essentially a travel and real life adventure writer who was initially far more famous than his now illustrious younger brother Ian Fleming, the creator of James Bond (and Chitty Chitty Bang Bang!). After his education at Eton and Oxford, Fleming first came to fame after participating in an intrepid journey through the Amazon basin, that had been undertaken to search for the lost British explorer, Colonel Fawcett. The subsequent book that Peter Fleming wrote about his experiences, his first, ‘Brazilian Adventure’, was published in 1933 and made his name. It is still in print. His next two books ‘One’s Company’ (1934) and ‘News from Tartary’ (1936) documented his rail journey from Moscow to Beijing and then his overland trek from China to India, in the company of a French female travel writer who he met along the way.

In 1940, Peter Fleming published a light-hearted novel ‘The Flying Visit’ , with illustrations by the celebrated New Zealand-born cartoonist David Low. The book describes an accidental visit to wartime Britain by Adolf Hitler. It eerily foreshadows the real flight of Rudolf Hess to Scotland in 1941.

After distinguished service in the Second World War, where Peter Fleming served in the first commando unit in Norway, and was involved in intelligence and deception of the enemy in South East Asia, he continued his writing career, producing another dozen or so books of travel, essays and novels, but became completely overshadowed by the growing fame of his brother Ian through the late 1950s and 1960s.

Peter Fleming was married to the famous British actress Celia Johnson, imortalised by her starring performance in the film ‘Brief Encounter.’ They had three children.

The official biography of Peter Fleming was written by his godson, Duff Hart-Davis, the son of the publisher of ‘Invasion 1940’, Rupert Hart-Davis.

Further reading

‘Brazilian Adventure’ by Peter Fleming, Alden Press, (1933)

‘One’s Company’ by Peter Fleming, Jonathan Cape, (1934)

‘News from Tartary‘ by Peter Fleming, Jonathan Cape, (1936)

‘The Flying Visit’ by Peter Fleming, Jonathan Cape, (1940)

‘Peter Fleming, A Biography’ by Duff Hart-Davis, Jonathan Cape (1974)

============================================================

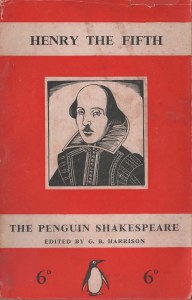

The Works of Shakespeare in Penguin

|

| Penguin B3 April 1937 |

The complete works of William Shakespeare were published by Penguin books in 37 volumes between 1937 and 1959, with a long hiatus between the 18th and 19th volume caused by the Second World War.

The first six volumes were published in April 1937 and were numbered B1- B6, even though the Shakespeare series predated by one month the start of the Pelican series, which had been given the A numbers. The whole series was edited and prepared by Dr. G B Harrison, who also provided the notes for each volume.

The first 21 volumes were published in red covers designed by Edward Young, who had designed all of the original Penguin covers. The front cover was decorated with a black and white woodcut of Shakespeare by Robert Gibbings. This was the first series published by Penguin to have an image on the front cover rather than pure typography. The first 18 books were published in dust jackets in three blocks of six each in April 1937, August 1937 and April 1938. The last three books with the original red covers, B19, B20 & B21, were published without dust jackets after the war in September 1947.

The series was renewed and completed by the publication of volumes B22 to B37 in a new black and white cover, designed by Jan Tschichold as part of the Penguin renovation project. These volumes carried a new wood engraving of Shakespeare by Reynolds Stone on the front cover, which was repeated on the title page. Volume B22 was published in October 1951 and the series ended with volume B37 which was published in September 1959.

Volumes B1 – B18 were priced at sixpence each (1937 – 1938).

Volumes B19 – B21 were priced at 1 shilling each (1947).

Volumes B22 – B25 were priced at 2 shillings each (1951 – 1954).

Volumes B26 – B37 were priced at 2 shillings and sixpence (1955 – 1959), with the exception of volume B36, Henry VI, parts 1, 2 & 3 which was published in March 1959 and was priced as a double volume at 5 shillings.

My list of the Penguin Shakespeare series B will be found here.