An Approach to the Investigation of Books

Introduction

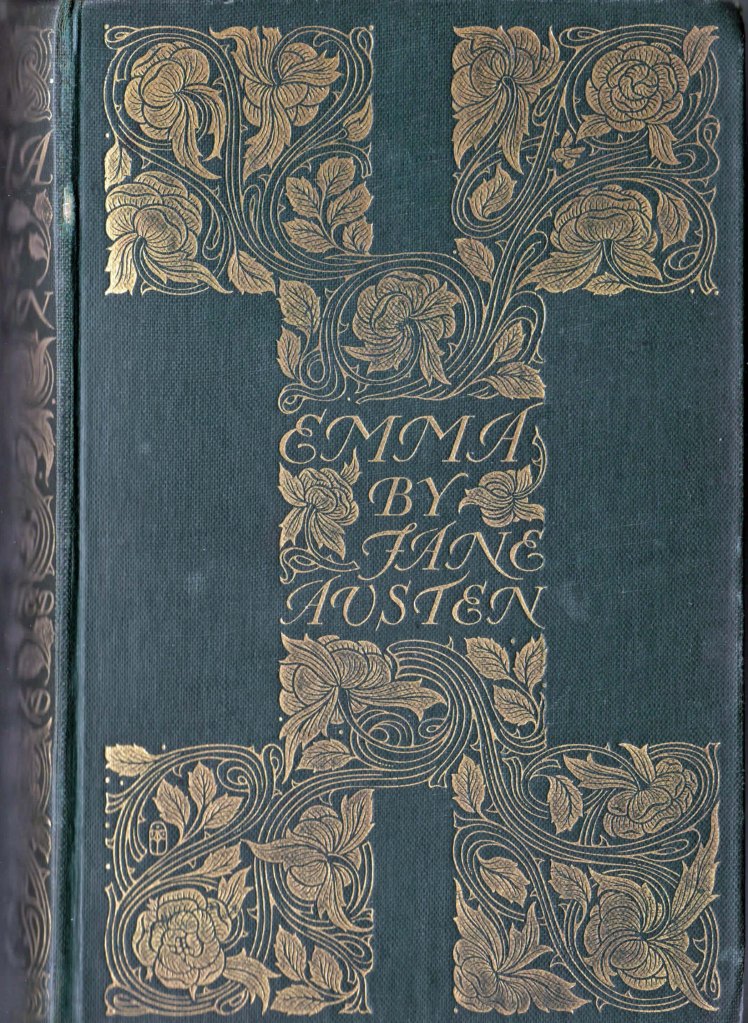

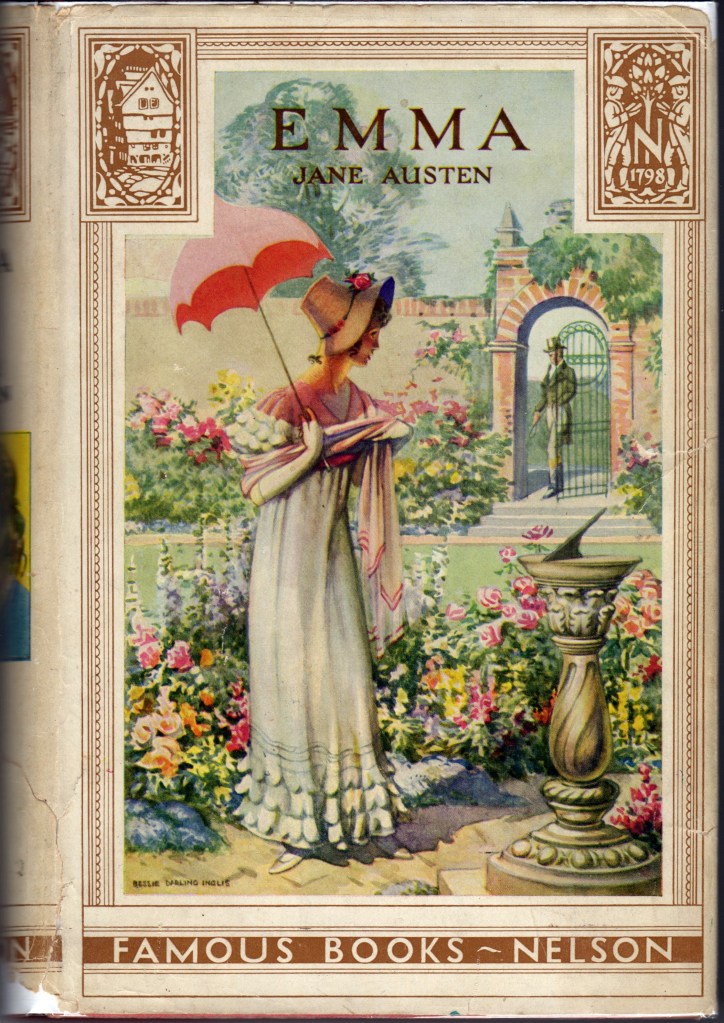

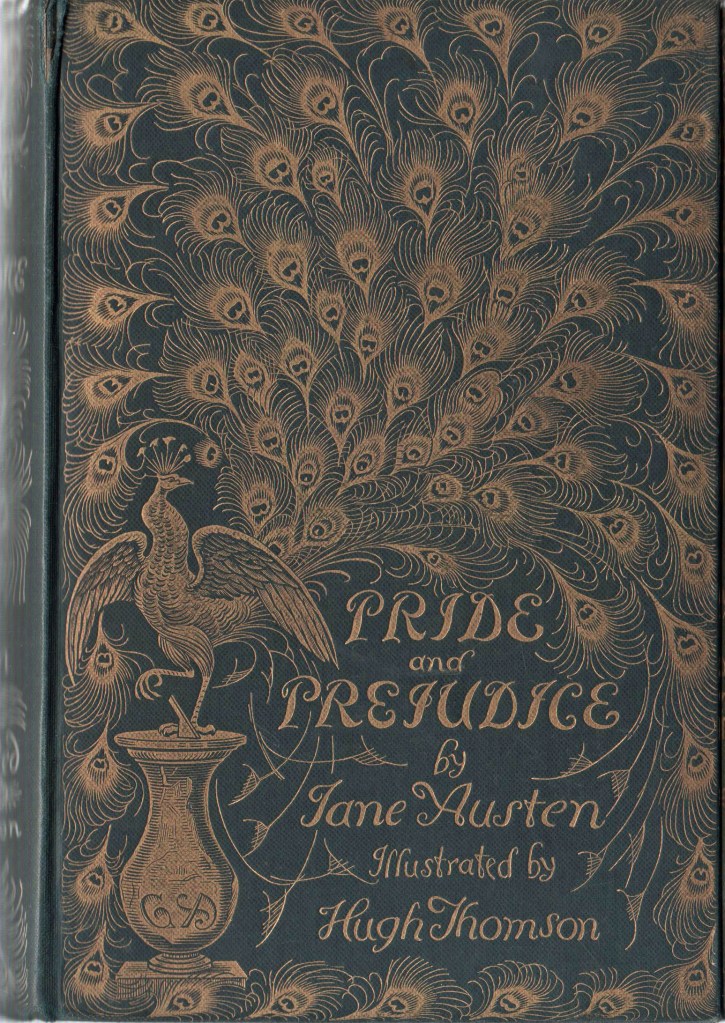

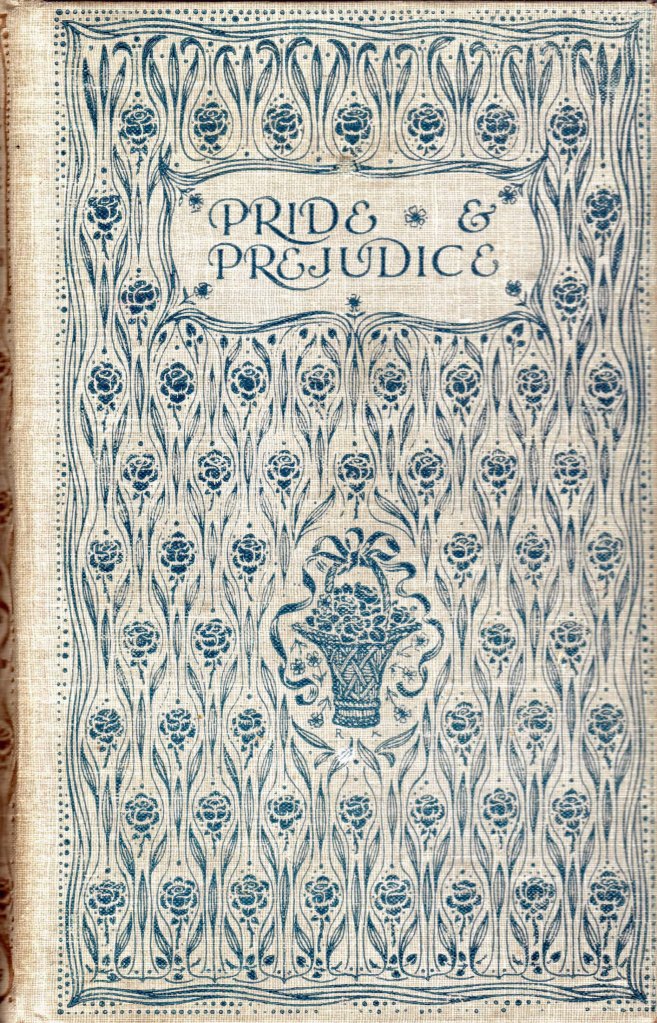

This is the starting point for a series of posts about how to find out information about any particular copy and any particular edition and printing of an old book. As a book collector, these have been topics of great interest to me, so I thought that it might be useful to share and document some of my approaches, methods and findings. I call this series “Price and Provenance” as it is often quite difficult to find out how much an older book initially cost and also who has owned it previously. Both are issues of some interest to a serious book collector. I am taking different editions of the novels of Jane Austen as my starting point for this series of posts, partly as it reflects one of my main collecting interests, and partly as I have quite a few interesting editions to discus.

New books

Let’s start with the situation of new books. It is obviously so much easier to document the price, nature and provenance of a new book. You go to your local bookshop, or if you must, look at online vendors. Whichever way you choose, you browse around the available stock, choose your book, pay your money and take your purchase home so it can join the family of your previous purchases.

Virtually all new books today carry excellent documentation of what they are. Externally, books generally will have a removable price sticker that humans can read and also often a machine readable price bar-code. For most of the 20th century, the price was recorded on the front inner, lower corner of the dust jacket, often below a diagonal line which invited the discerning gift giver to remove the price with a pair of scissors. Dust jackets that have been mutilated in this way are generally referred to as “price-clipped”.

Books will have a title page, which will tell you the book title, author and publisher, generally in that order as you read down the page. It used to be that, through most the past 500 years, the date of publication appeared at the foot of the title page. Today, more often than not, the title page will not have the date of publication printed at the bottom. You will now have to turn the page to find it.

Now for some nomenclature which I will try to introduce gradually through these posts. We call the front of a leaf in a book or right hand page as we view an opened book the “recto” and the rear of that page, normally appearing on the left hand side of an opened book, the “verso.” So, if you look on the other side, the verso, of the title page of a new modern book, you will see a whole lot of detail which gives you a full description of the book. There will be a dated copyright statement, the date of publication, and the full name and address of the publisher, often with addresses of that publisher in multiple countries. Books published in the USA will have a statement about registration with the Library of Congress. In the UK, the equivalent is a statement about a CIP catalogue number registered with the British Library, and in Australia, where I live, there will be an equivalent statement with regard to the National Library of Australia. Towards the bottom of the page the details and address of the printer are usually given.

The details of the edition of the book also generally appear on the verso of the title page. Some times the statement will be simply “First Edition” ; other times it might say “Third impression” or it might read something like “First published in 1963, reprinted 1964 (twice), 1965, 1966”. More recently, this has been codified into a line of numbers. It generally looks like this:

1 3 5 7 9 10 8 6 4 2

or this: 1 3 5 7 9 8 6 4 2

But is may also look like this: 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

All of these tell you that the book is the first impression (printing) of the first edition. If however the line of numbers should look like this:

9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2

you are dealing with the second impression of the first edition, and you will find with each new impression, a further digit is removed. For some blockbusters, the publishers just print a number by itself to indicate the impression.

International Standard Book Number (ISBN)

In modern books, you will also find the ISBN number. ISBN stands for International Standard Book Number. These started in 1965 as a nine-digit Standard Book Number which in 1967 became the International Standard Book Number. The format was officially established as an international standard in 1970 when a ten-digit ISBN was adopted; the earlier nine-digit numbers were updated by the addition of a leading zero. New books displayed the ten-digit ISBN, as a printed number or as a bar-code from 1970 until 2007 when the ISBN standard was redefined as a 13 digit number. While most countries adopted the ten-digit ISBN in 1970, the UK persisted with the nine-digit format until 1974. Most book readers will be familiar with the appearance of the 13 digit ISBN bar-code format shown below:

Without going into the full complexities of the ISBN system, the principle is that each book should be uniquely identified, just as a URL uniquely identifies a Web page. The structure of the ISBN is built from several elements: a three-digit prefix, currently 978 or 979 known as the EAN (European Article Number), the language and or country of publication, publisher and book details. The final single digit is a technical check-sum. The elements are separated by blank spaces or by hyphens. Different formats of books (hardback, paperback, e-book) each get their own individual ISBN.

Identification and provenance of older books

For any book published before 1970, there is no ISBN, so as collectors, we have traditionally concentrated on the identification of the precise edition, printing or binding of any given book, either from inspection of the book itself, or by recourse to catalogues and bibliographies. Much less effort has been expended on understanding provenance, with the exception of the identification and collection of desirable “Association” copies of books. By Association copy, we mean a book which has been previously owned or inscribed by someone of importance, either to the book itself, or its subject matter or sometimes just by the personal fame of the associated person.

In her recent excellent book “The Lost Novels of Jane Austen”, (Johns Hopkins University Press, Baltimore, 2019, ISBN 978-1-4214-3159-8) Professor Janine Barchas explores the topic of the provenance of hitherto unregarded, cheaper editions of the novels of Jane Austen as valuable evidence in the understanding of how the popularity of this major author was spread by the publication of editions that were accessible to the broad general reading public. Many of the books that she examined had escaped inclusion in the standard bibliographies.

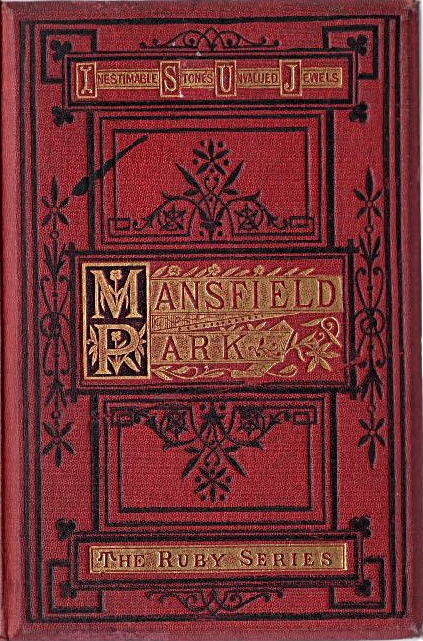

Professor Barchas also uses the information of prior ownership, in combination with family history research techniques, to rediscover some of the countless unrecognised readers of Jane Austen from the past. This approach has been a facet of my book collecting practice for the past decade or so. In a series of follow-up posts, I will share some of the findings of my exploration of provenance and the previous history of the books in my collection. My first examples, like Janine Barchas’ work, will involve Jane Austen. Here are three copies of Mansfield Park which I will be exploring first.

Read the next posting to learn more about these three books.