Richard Bentley, London: New Burlington Street

For more background information of the Bentley editions of Jane Austen, please read the first few paragraphs of the article on Bentley edition of Emma, Gilson D2.

Sense and Sensibility, along with the other five novels of Jane Austen that had been published between 1811 and 1817, did not appear in a new English edition until Richard Bentley decided to reprint all of the Austen novels as “Standard Novels” in 1832. The first edition of Sense and Sensibility had been published in 1811 followed by the second edition in 1813, both published by Thomas Egerton in 3 volumes. Sense and Sensibility was published by Richard Bentley on 28th December 1932, for 6 shillings. Sense and Sensibility was numbered “XXIII” (23 ) in the Standard Novel series. It was the third edition of Sense and Sensibility to be published in the UK, the first single volume edition, the first edition to have any illustrations and the first to have Jane Austen’s name as author on the title page(s). Standard Novel XXIV (24) was a translation of Madame de Stael’s Corinne, which appeared on February 1st 1833. An announcement of the intended publication of Corrine by Bentley on this date appears on the verso of the series title page of Sense and Sensibility (Figure 1). Although the publication date of Sense and Sensibility was on 28th December 1832, Bentley printed 1833 on all of the dated pages, a common practice by publishers, who used this practice to extend the apparent currency or newness of their books.

Figure 1: (left) Series title page for Gilson D1 Bentley’s Sense and Sensibility 1832

Figure 1: (right) Verso of Series Title page showing announcement of Corinne.

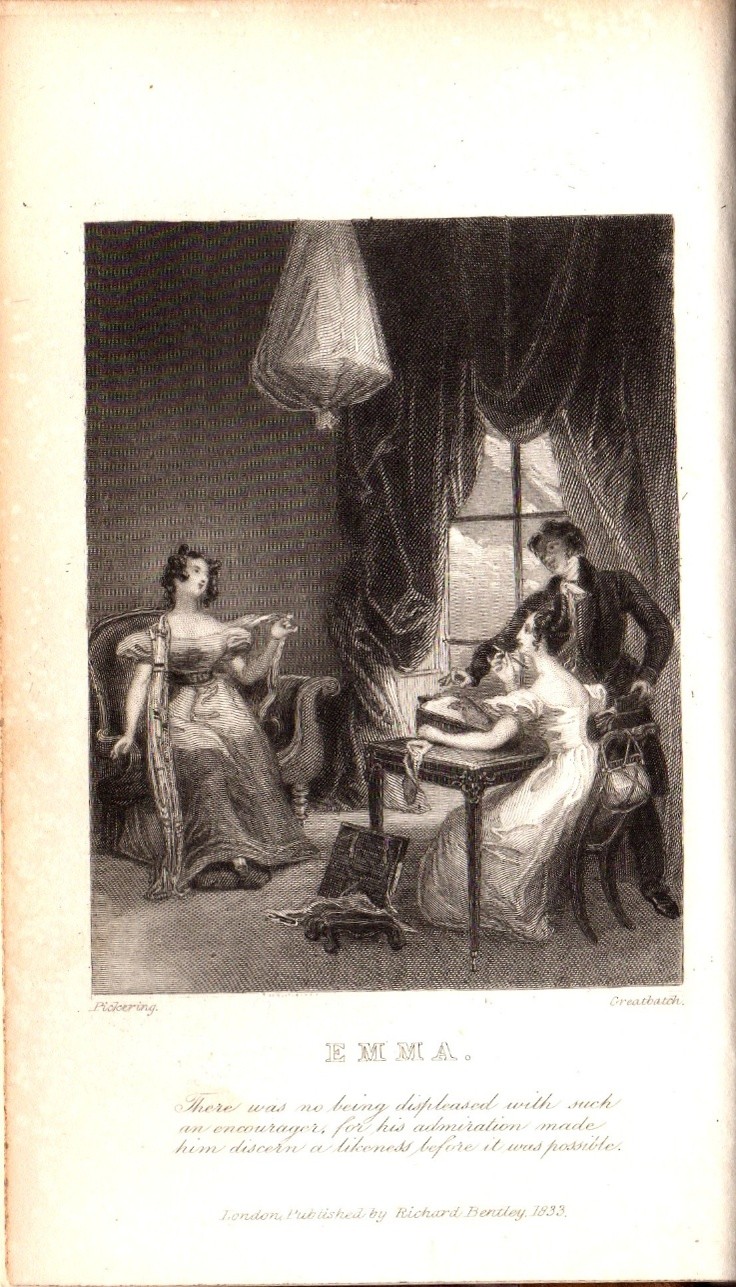

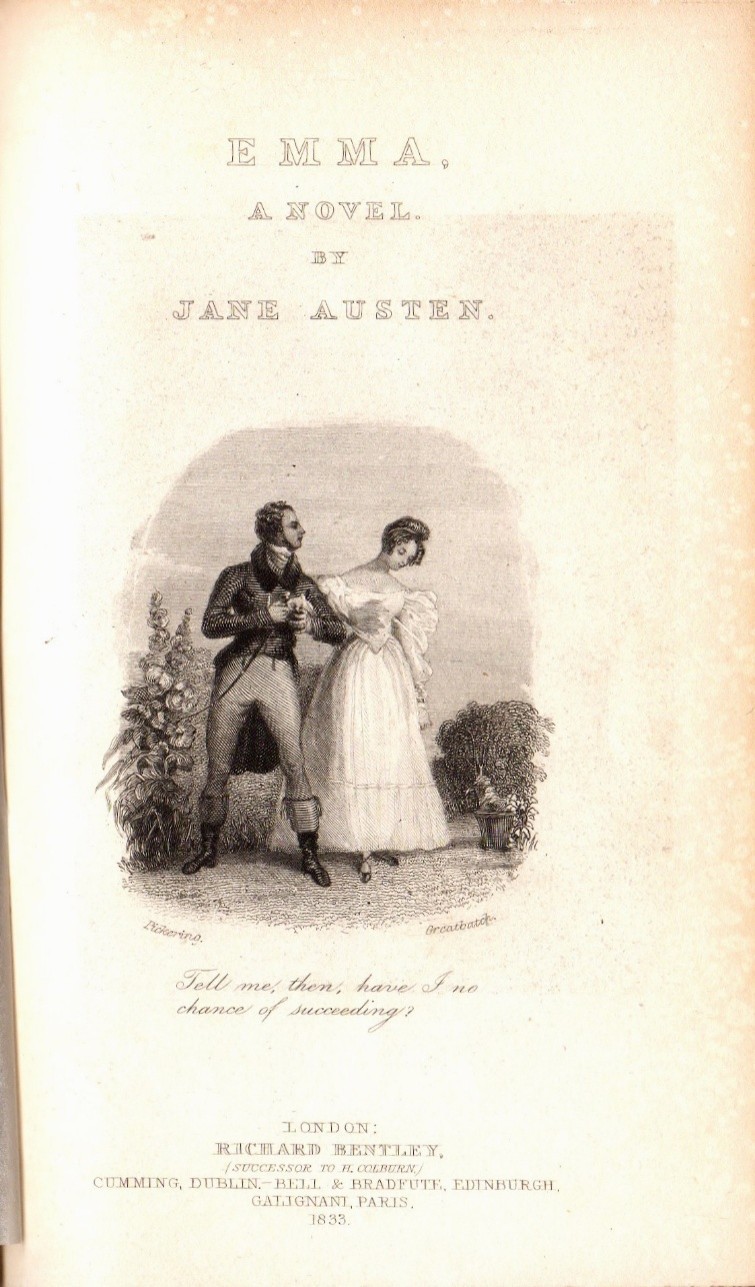

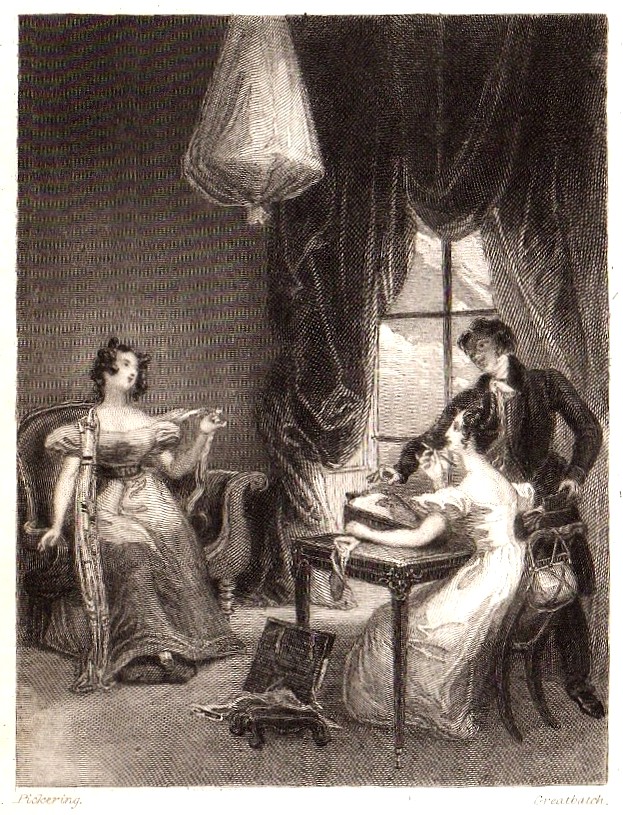

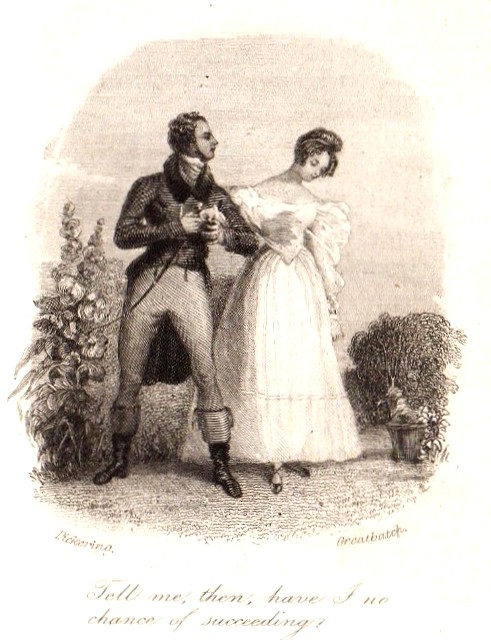

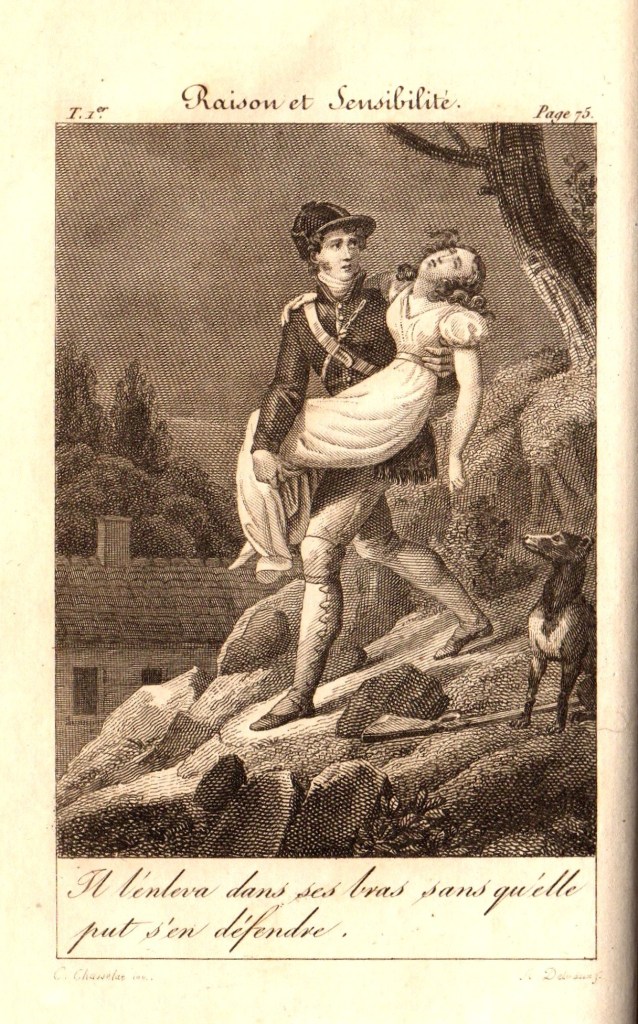

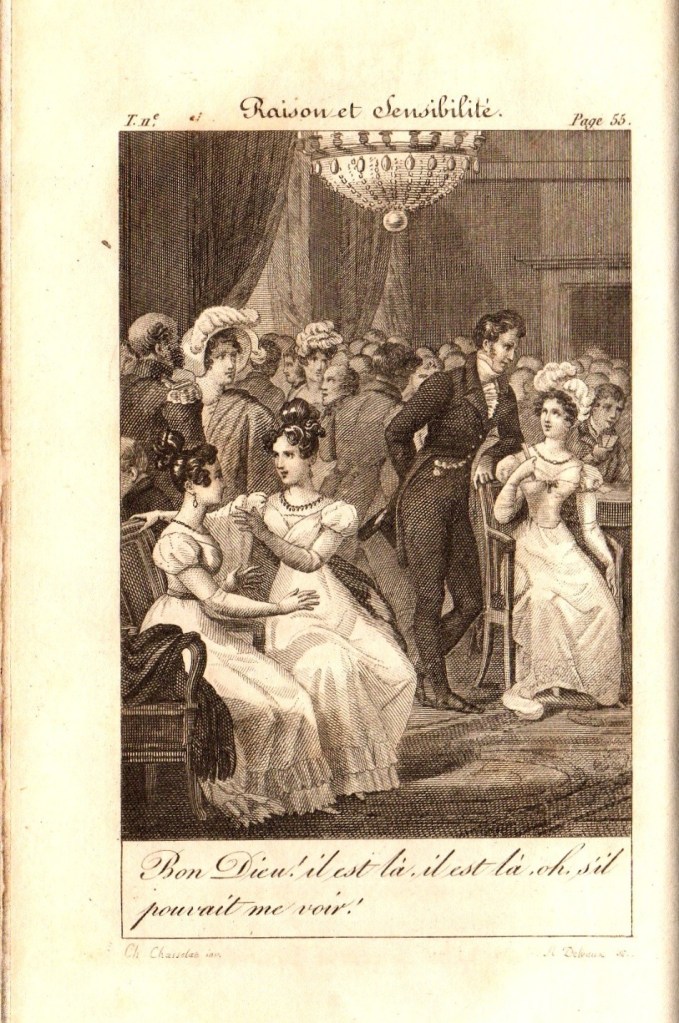

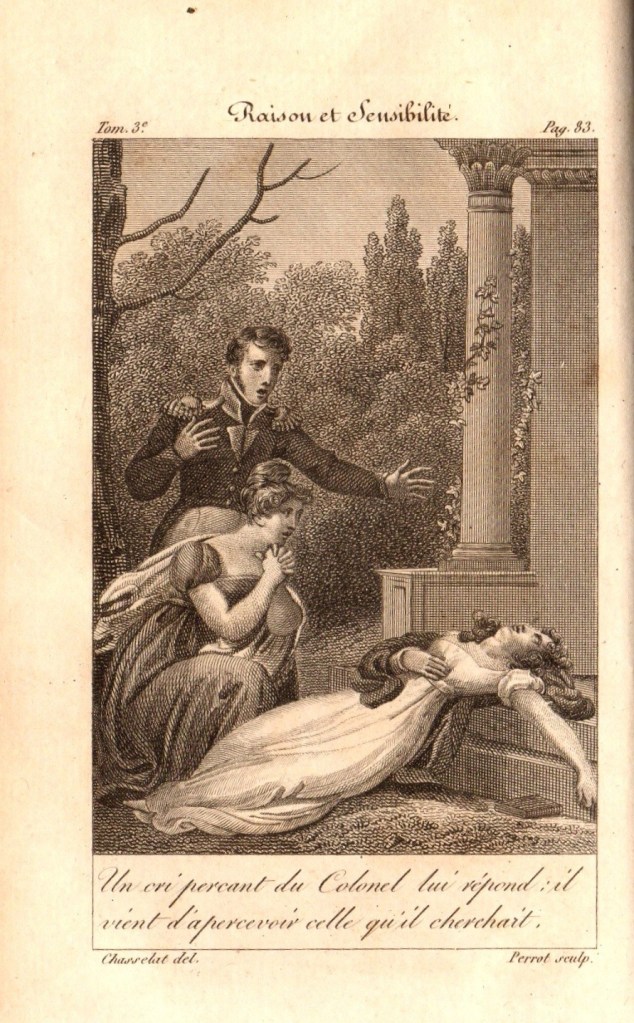

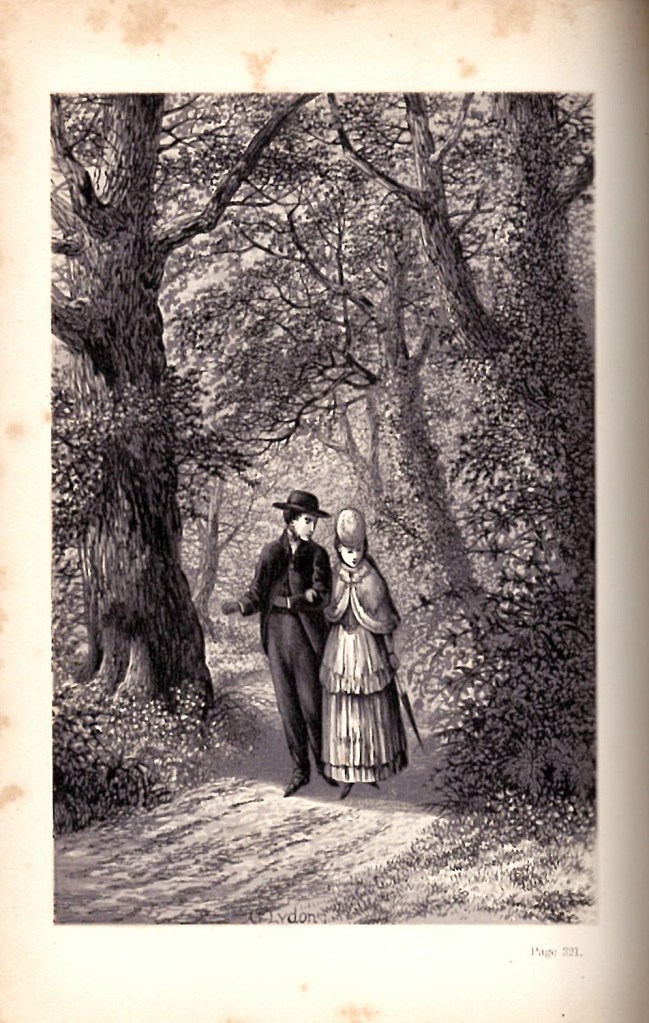

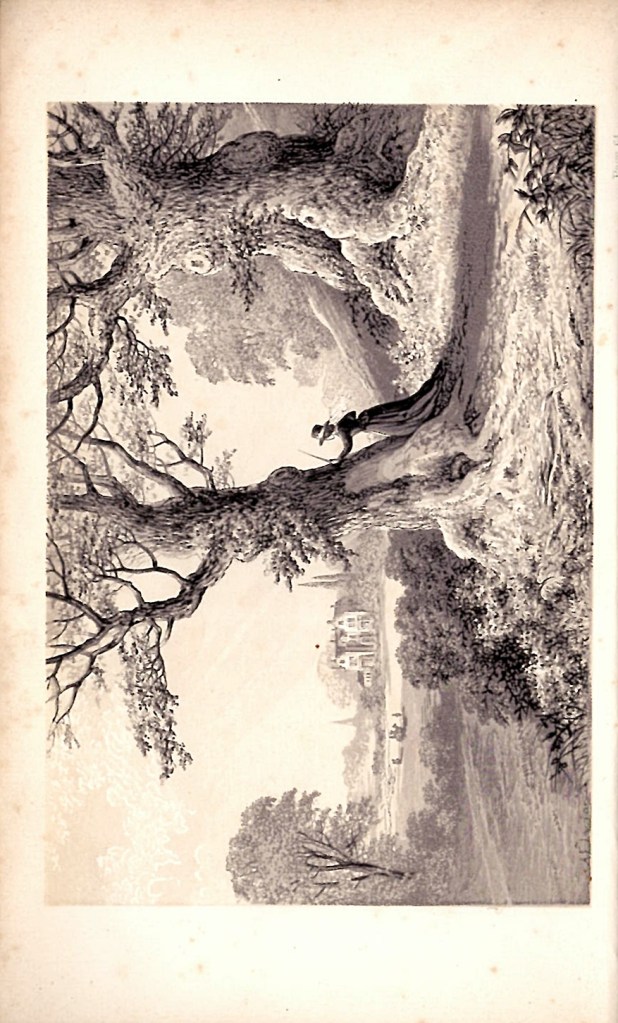

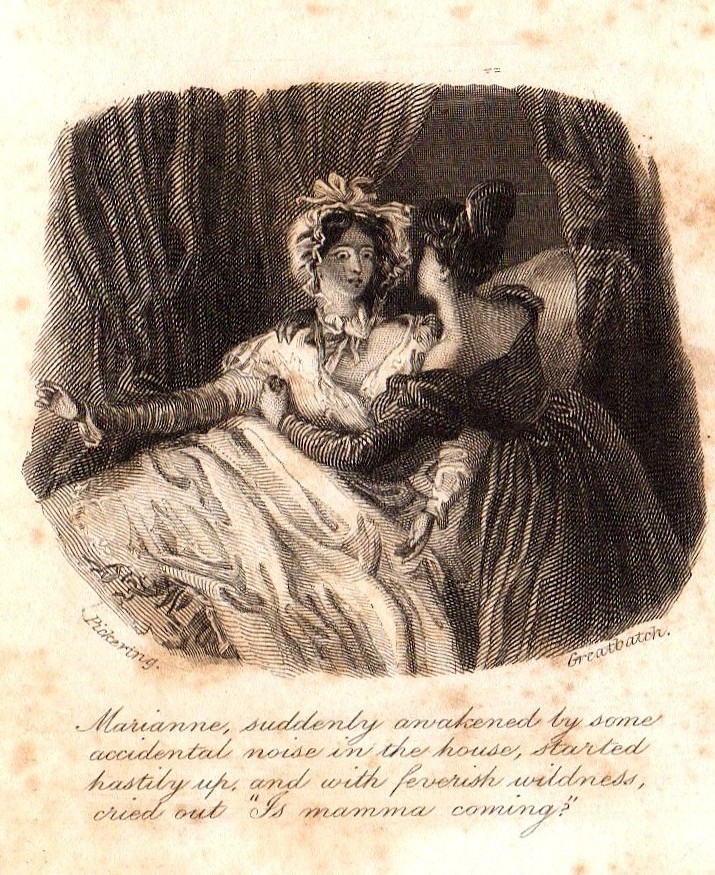

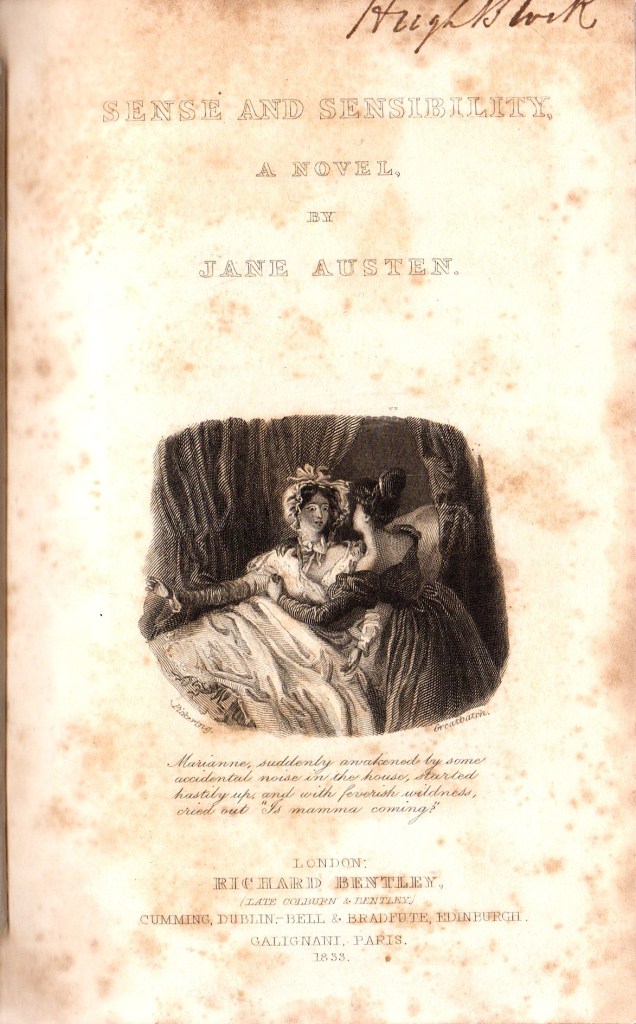

In Figure 2, the two illustrations for the Bentley edition of Sense and Sensibility are presented as the frontispiece on the left and the engraved title page vignette on the right. They are both drawn by Ferdinand Pickering and engraved by William Greatbatch, as is the case for all of the illustrated Bentley editions of Jane Austen’s novels. The images show figures in costumes appropriate to 1832, rather than to the earlier period when the book was written. The frontispiece shows the incident from Chapter 22 of Volume 1, where Lucy Steele is showing the miniature of Edward Ferrars to Elinor Dashwood. The text under the image reads as follows: Then taking a small miniature from her pocket, she added “To prevent the possibility of a mistake, be so good as to look at this face.” This is a slight misquotation of the original text on page 133 which reads “possibility of mistake”.

Figure 2. Frontispiece (left) and vignette (right) illustrations from Gilson D1

The vignette on the right of Figure 2 shows Marianne Dashwood suddenly awakening, startled and arising from her sickbed, held by her sister Elinor (from Volume 3, Chapter 7). The text reads: Marianne suddenly awakened by some accidental noise in the house, started hastily up, and with feverish wildness, cried out “Is mamma coming?”

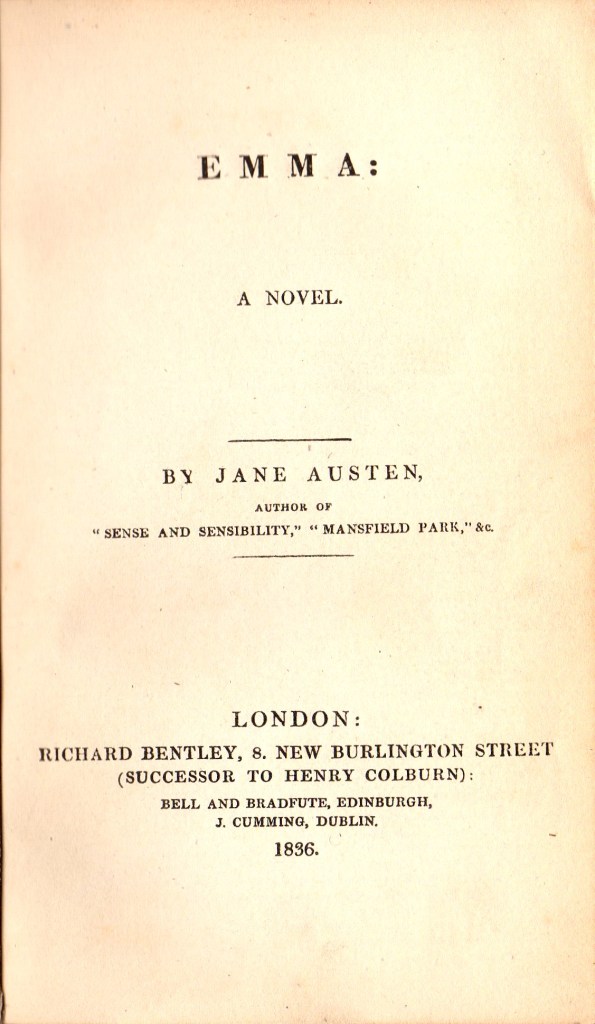

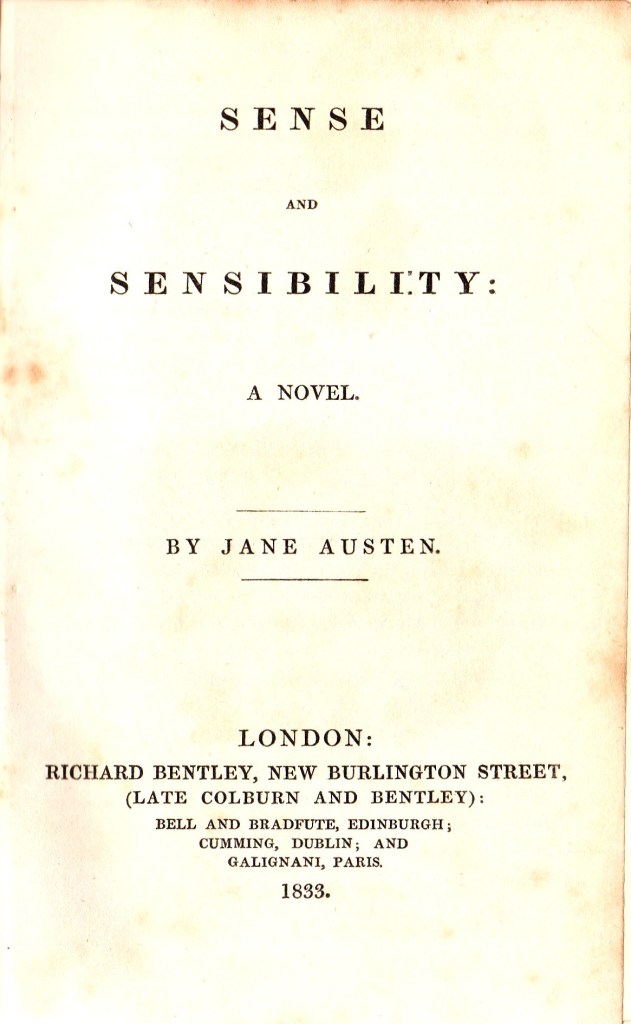

The full engraved title page and the letterpress title page are shown in Figure 3 below. Note that there are some small differences in the way that the publishers details are presented on these two pages. The dates on these pages shown in figures 1, 2 and 3 are all presented as 1833, rather than 1832. There is an inscription of a previous owner of the book, “Hugh Block”, on the top of the engraved title page.

Figure 3. The engraved (left) and printed title pages for Sense and Sensibility Gilson D1

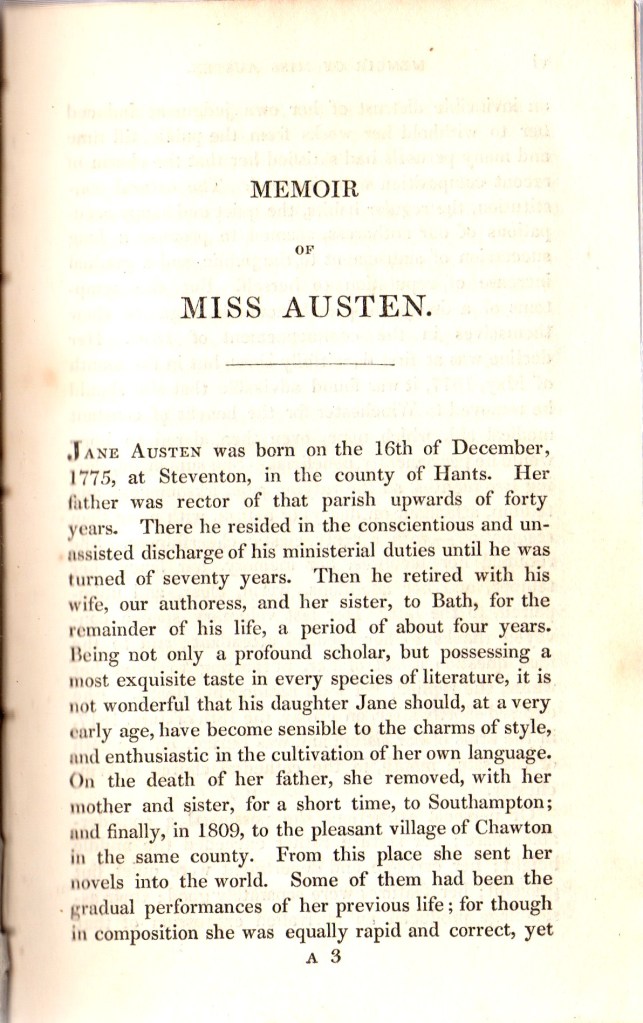

Immediately following the printed title page, Bentley presents a “Memoir of Miss Austen” which is on the preliminary pages (v) to (xiv), that is p5 to p14 in roman numerals. The memoir is unsigned and dated October 5th 1832. It has been described elsewhere as by “the Rev. Mr. Austen”, which would have been the author’s brother Henry Austen. The first part of the Memoir is an edited and revised version of the “Biographical Notice” published by Murray as a preface to the posthumous edition of Northanger Abbey/Persuasion in 1817, which is itself dated December 13th 1817. This was also generally agreed to have been written by Rev. Henry Austen. The second part of the Memoir, running from the bottom of page (x) to page (xiv), pages 10-14), are taken from a review of Northanger Abbey/Persuasion published in the Quarterly Review of January 24th 1821.

The final page of the “Memoir” is a note from the editor of Gilson D1, presumably Richard Bentley himself, which announces that the other novels of Jane Austen will follow in the Standard Novels series. The editor also comments on the importance of Jane Austen, cites the related novels of Madam D’Arblay (Fanny Burney), Miss (Maria) Edgeworth, Mrs. Opie and Miss Porter, and praises Jane Austen for “the truth, spirit, ease and refined humour of her conversations” , and her ability “to make the veriest every-day person a character of great interest.”

Figure 4 show three pages from the “Memoir” section of Gilson D1.

Figure 4. Pages v, x and xi from the Memoir of Miss Austen

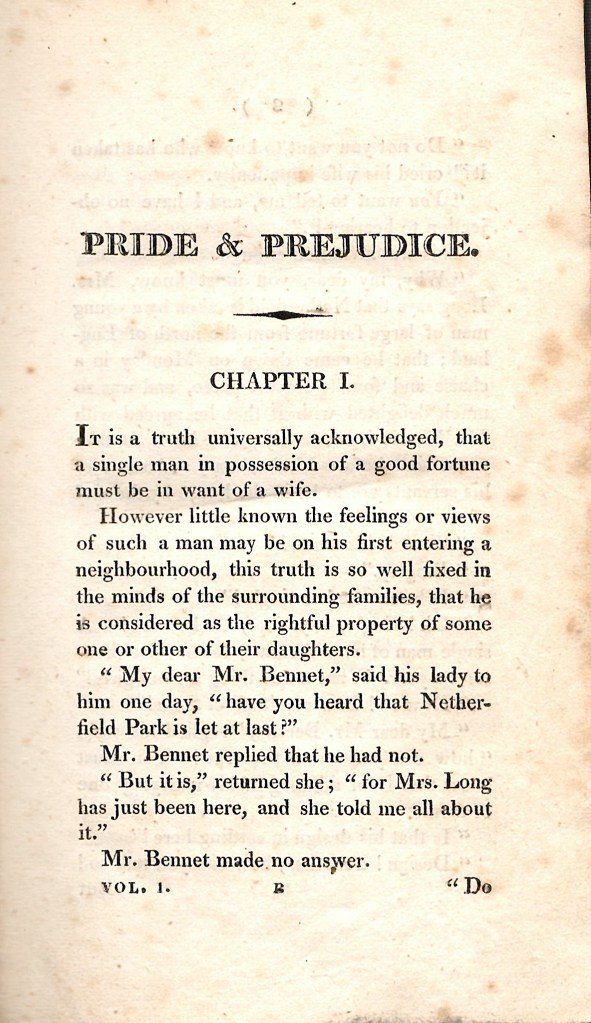

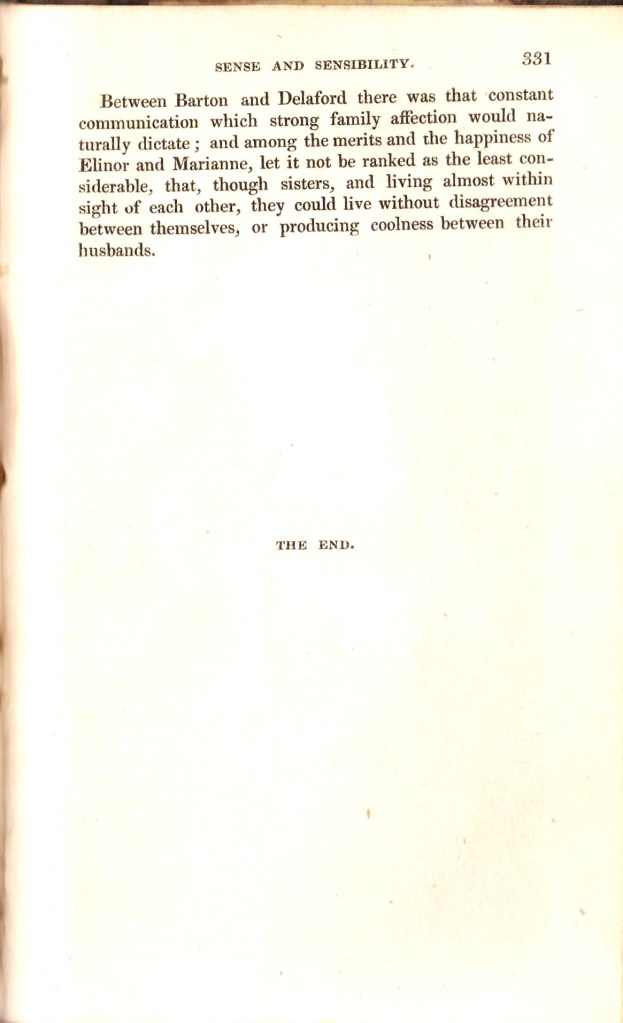

Richard Bentley arranged the text of Sense and Sensibility to correspond to the same chapter and volume arrangement as in the first and second editions. Accordingly, the book remains divided into 3 volumes, with Volume The First consisting of 22 chapters occupying pages 1-116; Volume the Second has 14 chapters running through pages 117-219 and Volume the Third also has 14 chapters running from page 220 to the final page 331. Throughout the book, most of the chapters do not start on a new page, and are separated by a simple centrally placed ruled line about half the width of the page. The chapters are numbered in large Roman numerals, whereas the page numbers are printed as Arabic numbers at the outer top corners of the pages. The first and last pages are shown in Figure 5 below.

Figure 5. Pages 1 and 331 of 1832 Bentley edition of Sense and Sensibility

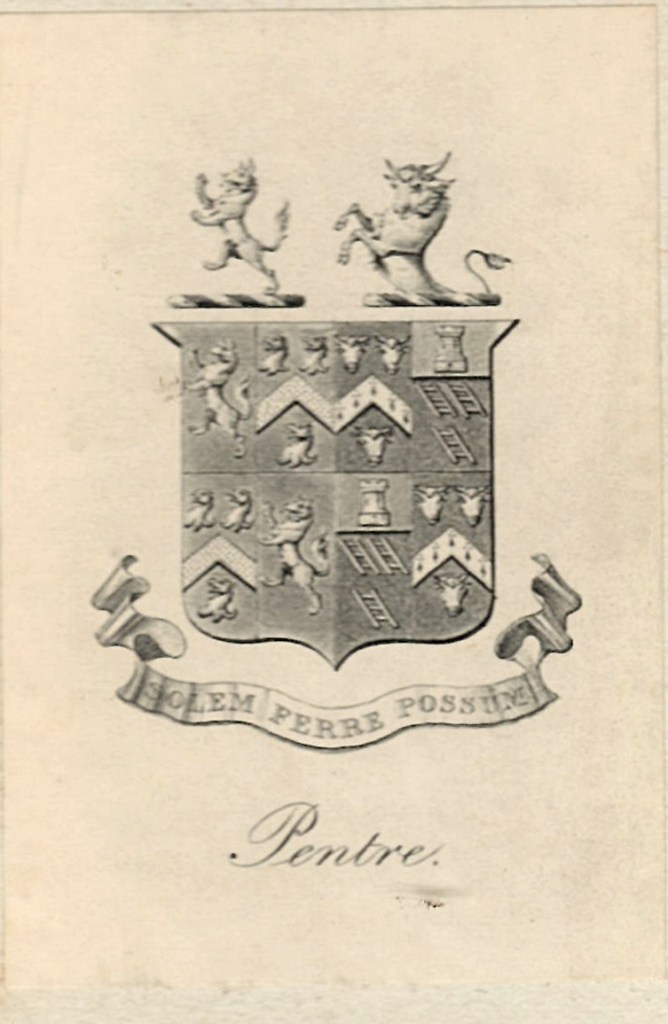

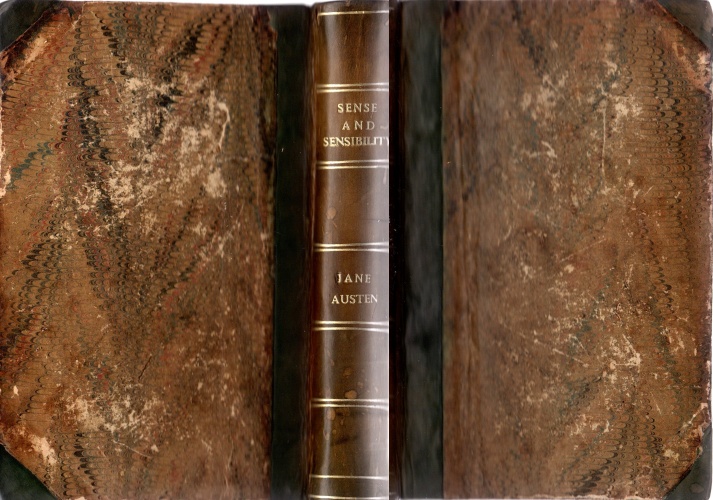

Gilson D1, Sense and Sensibility, would have been originally bound in plum-coloured, glazed linen boards, with black labels on the spine which were printed in gold. This binding was used by Bentley for the Standard novels issued between 1831 and 1838, and is generally called Sadlier style 1. Examples of this can be seen in my copies of Mansfield Park (Gilson D3) and Northanger Abbey/Persuasion (Gilson D4). However, my copy of Sense and Sensibility has been rebound in marbled paper-covered boards, half-bound in green morocco with gilt labelling on the spine in two gold lined compartments (Figure 6) . The spine has faded from green to light brown. The binding looks mid-19th century, but has recently been rebound, with the addition of new yellow endpapers.

Figure 6. Binding of my copy of the Bentley edition of Sense and Sensibility.

Later reprints of Bentley’s Sense and Sensibility Gilson D1

The 1832 issue of Bentley’s first edition of Sense and Sensibility shown in this article is the only issue that I currently have of this Standard Novels edition, I do also have a copy of the 1856 issue, which is as a part of a set of The Novels of Miss Austen (Gilson D6). There are other known reprinted issues of Bentley’s Sense and Sensibility that appeared in 1837, 1846, 1853, and 1854 in the Standard Novels series, all designated Gilson D7, and a further reprinted set of Gilson D6 in 1866. A “New Edition” of Sense and Sensibility is published by Bentley in 1970 as Gilson D8. That is the subject of a separate article in this series.

Return to the Index page for Illustrated Editions of Jane Austen.